Is Drought Slowing Down the Christmas Tree Industry?

According to recent news reports (USA Today, WJHG, Wilkes Journal-Patriot), the United States has been experiencing a nationwide Christmas tree shortage, along with price hikes as a result of low supplies. The U.S. Christmas tree industry is a $2 billion a year industry, according to annual reports from the National Christmas Tree Association.

According to recent news reports (USA Today, WJHG, Wilkes Journal-Patriot), the United States has been experiencing a nationwide Christmas tree shortage, along with price hikes as a result of low supplies. The U.S. Christmas tree industry is a $2 billion a year industry, according to annual reports from the National Christmas Tree Association.

Many of the major Christmas tree exporter states - which include Oregon, Washington, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania - are struggling with a number of short and long-term challenges for production, including the 2008 recession, Phytophthora Root Rot, difficult harvest weather, and drought.

However, digging a bit deeper reveals a much more complex story about drought and weather - and about this year’s Christmas trees. According to Doug Hundley, spokesperson for the National Christmas Tree Association, fewer trees were harvested and sold this year, but there hasn’t actually been a shortage.

“What we do have is a good balance between supply and demand, now. From 2005 to 2015, we had a small but significant excess in supply. So, today, in people's minds, we have a shortage now - but really, we just have a good balance; when supply surpasses demand, unsold trees are thrown away” says Hundley. Gary Chastagner, Plant Pathologist & Extension Specialist at Washington State University, adds that “there may not be as many large trees available today as there were five years ago, but there is a fairly reasonable assortment of trees.”

While there may not be an actual shortage of Christmas trees this year, the industry is starting to see reductions in the quantity of trees placed on the market, as well as a smaller proportion of large trees that are available. Multiple factors are playing a role in this decline - including both drought and too much precipitation.

DROUGHT IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST

Prolonged drought can have major agricultural impacts, including harm to long-term crops like Christmas trees. Currently, more than half of the Pacific Northwest is experiencing drought, due in part to this year’s dry summer and late winter. “Oregon and Washington normally provide 30% to about 40% of the Christmas trees in the nation, and they’re suffering from these successive dry years, and I know they’re having trouble getting fully re-planted,” said Hundley.

Chastagner agrees. “We’ve clearly had very dry summers the last couple of years. So if you’re trying to grow an agricultural crop, particularly in areas like the Pacific Northwest where the growers do not irrigate their fields during the summer, that can be an issue. Dry conditions have an effect largely on survival of [Christmas tree] seedlings that have just been planted in the field.”

Hundley adds, “When you have a loss of a lot of seedlings in a given year, the growers will try to replant those the next year. But let’s say that there’s a two or three-year drought, and they’re losing 30% a year. They could be losing time—significant time—when drought is repetitive.”

However, according to Chastagner and Hundley, this year’s drought and the last couple of dry years in the Pacific Northwest, would not have much of an impact on this year’s Christmas tree industry. “Crops such as Christmas trees generally are not irrigated because of the ability of those crops to withstand periods of dry soil - which is a good thing,” said Chastagner. The availability and quality of larger trees would not be impacted by recent drought conditions, “but it may have an effect down the road, if you have a few years where you have poor seedling survival.”

It takes about seven to ten years for Christmas trees to reach maturity, according to Hundley, and once the trees reach three to four feet tall, they become much more resilient to dry conditions. “If we can get them established for a couple of years with enough rainfall, they can usually handle droughty conditions after that. They may not grow as much as they would grow with plenty of rain - but they usually survive.”

Growers also stagger their tree fields to make them more resilient to hazards like drought and disease. According to Chastagner, “Usually, trees are harvested over a three-year period, so they have trees of all different sizes and ages in a given field. So if you have a condition where you have poor seedling survival for a year at a given site, usually there is enough wiggle room in the system that the grower can deal with those problems, because there is enough overlap from one planting to another in harvesting.”

THE 2011-2012 DROUGHTS

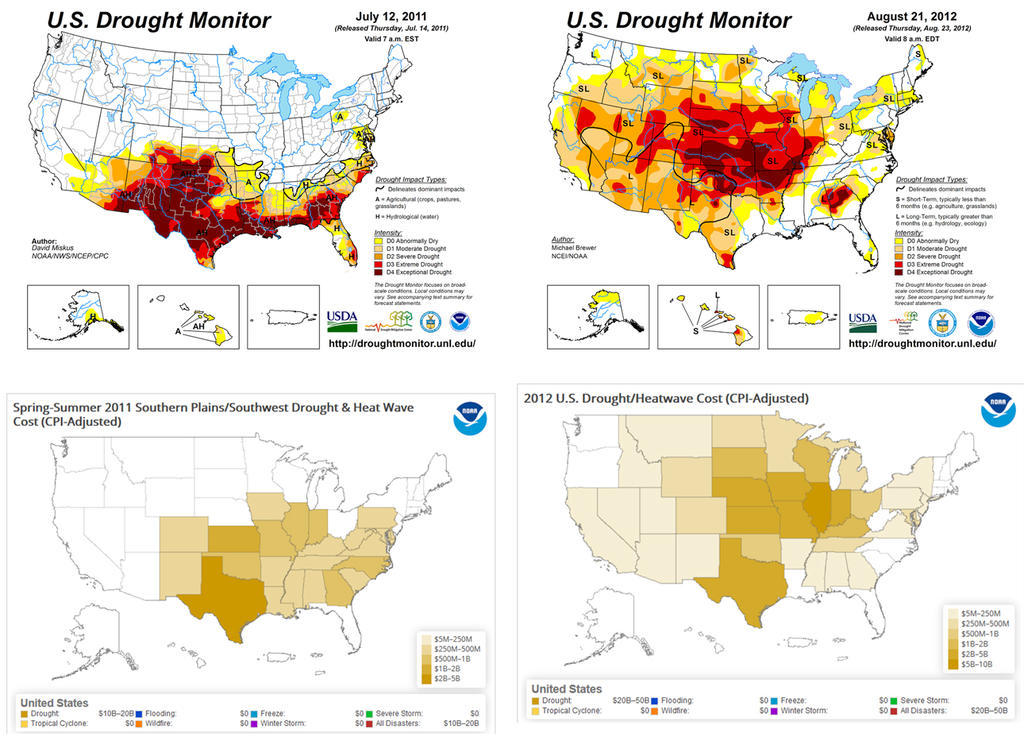

According to news reports (KEZI, KOLN/KGIN), it is actually the droughts of 2011 and 2012 that are partly responsible for this year’s reduction in Christmas trees. The droughts during 2011 and 2012 remain the most severe in recent history. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, on July 12, 2011, the largest expanse of Exceptional Drought (D4) was recorded with nearly 12% of the Continental U.S. experiencing the worst category of drought (since 2000). This record-setting drought spanned from June to November of 2011. In 2012, the country saw the most expansive occurrences of all other drought categories (D1/Moderate Drought through D3/Extreme Drought), lasting from July to February of 2013.

Both of these droughts caused significant impacts to agriculture and economies. According to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) Billion-Dollar Disaster report, the 2012 drought was the second-worst drought on record behind 1988, was linked to 123 deaths, and caused at least $33.3 billion in damage across more than 30 states. The 2011 drought was linked to 95 deaths and caused at least $13.7 billion in damage across 23 states.

What the Billion-Dollar Disaster report can’t account for, however, are impacts that take years to manifest. When calculating billion-dollar disasters, NCEI considers drought disasters to be regional-scale events that often range from six months to a year, with calculations stopping at the end of the calendar year. The assessments take into account the most severe, drought-related impacts, which are largely focused on crops and livestock costs.

“We do not capture losses to longer-term crops, like Christmas trees, for example, in which drought damage persists over years,” says applied climatologist Adam Smith, who leads NCEI’s Billion-Dollar Disaster program. “Effectively, our drought estimates should be considered conservative, given that all losses from drought are not captured in the data.” Seven years after the 2011 drought, there is growing concern that the delayed impacts of these past droughts are just now starting to be felt - particularly in the Christmas tree industry.

TOO MUCH MOISTURE

In terms of weather and climate, multiple years of drought can have long-term effects on the Christmas tree industry and on many other sectors of the economy and public health, but too much moisture can be just as devastating for Christmas trees.

“When it's really wet, and really cold, and really snowy, it gets really difficult to get the trees out,” says Hundley. “Looking at weather from all sides, that is certainly a short-term stress on the Christmas tree industry—harvesting in rough weather. This year just happens to be an outstandingly bad year for harvest conditions. The snow that just hit the southeast may have actually affected retail sales.”

While wet weather is having an effect on this year’s harvest, too much moisture in the long-term is also driving an epidemic in many of the major Christmas tree exporter states. Hundley explains, “We have a serious problem with Fraser Fir production because of a disease that loves wet weather - Phytophthora Root Rot. We lose our ability to grow Fraser Fir every year when it rains like this, and when I say lose it, what I mean is that we can’t grow the Fraser Fir on that site again. Ever. We may be able to grow another kind of Fir, but not the one that we’re known for. It’s a problem for all the states that grow Fraser Fir, where the rain has been excessive this year. We have both drought and excessive wet conditions - both create problems for Christmas trees.”

2008 ECONOMIC RECESSION

Magnifying the concerns about delayed drought impacts, the downturn of the economy in 2008 is also playing a role in the quantity of trees currently available. “Fewer trees were being planted at that time, a number of growers went out of business,” explained Chastagner. “Growers were holding trees in some cases because of less demand. When the market picked up, in some cases there were just not as many trees available.”

Sam Minturn, Executive Director of the California Christmas Tree Association, agrees, saying that the 2008 recession is now having an impact on supply and prices in the California market, which “will probably affect the California market for several years to come, and many of us growers worry that the increase in prices will drive customers to the artificial tree, which we feel is not a plus to the environment.”

LONG-TERM IMPACTS - A POTENTIAL SHIFT

Chastagner anticipates that continued long-term droughts may have an effect on how Christmas trees are planted and grown. “Long-term effect of drought varies,” he said. “Planting sites have different soil characteristics. One of those characteristics is the ability to hold moisture. If there is a protracted period of multiple years of drought, growers would have to, in some cases, be able to shift to sites that had better soils, as far as moisture-holding capacity. There are a few growers that do irrigate, but not too many. Some growers plant earlier in the season so the seedlings have a chance to establish their roots and are able to withstand drier conditions.

I do think growers are concerned about soil moisture status and moisture stress. There are likely to be some shifts if there are prolonged periods of hot, dry summers that would affect primarily seedling survival. It would cause a shift in how growers in the Pacific Northwest potentially have to grow their trees.”