New Report on Drought Assessment in a Changing Climate

Key Points:

- Climate change is causing the probability of extreme events, like drought, to change, a phenomenon known statistically as “non-stationarity.”

- Challenges include identifying the differences between permanent change (e.g., long-term trends towards wetter or drier conditions) and temporary anomalies from normal conditions (e.g., drought).

- Changes in how we assess drought could impact disaster relief and adaptation programs and inform future policy.

- To improve drought assessment, the report identifies priority actions and research questions organized around 15 focus areas.

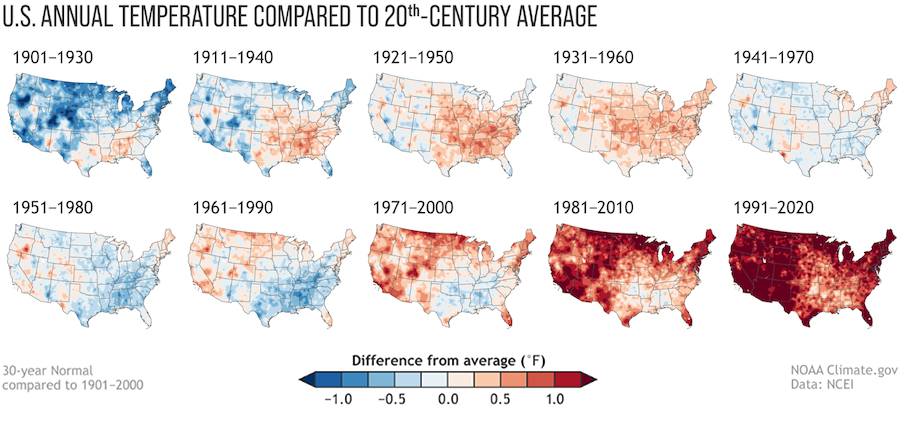

According to the American Meteorological Society (AMS), drought is defined as “a period of abnormally dry weather sufficiently long enough to cause a serious hydrological imbalance. To assess “abnormally dry weather,” there needs to be a standard of “normal” to act as a comparison. However, establishing what time period should be used to constitute “normal” is not straightforward. In a changing climate, past human experience is not always an indication of what to expect in the future. The changing climate is causing the probability of extreme events, like drought, to change, a phenomenon known statistically as “non-stationarity.”

The changing climate is causing the probability of extreme events, like drought, to change, a phenomenon known statistically as “non-stationarity.”

Non-stationarity poses new challenges that include identifying the differences between permanent change (e.g., trends towards wetter or drier conditions) and temporary anomalies from normal conditions (e.g., drought). To address these challenges, NOAA’s National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) and USDA Climate Hubs released the report, Drought Assessment in a Changing Climate: Priority Actions and Research Needs. Additional support for the workshop and report was provided by the University of Colorado Boulder 's Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES).

The report captures the ideas and feedback of more than 100 subject matter experts from over 44 institutions across the drought research and practitioner communities. This report includes a state of the science overview on drought in a changing climate and identifies some of the most pressing and strategic areas of research and action to advance the knowledge and understanding of drought assessment.

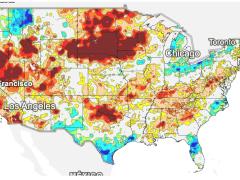

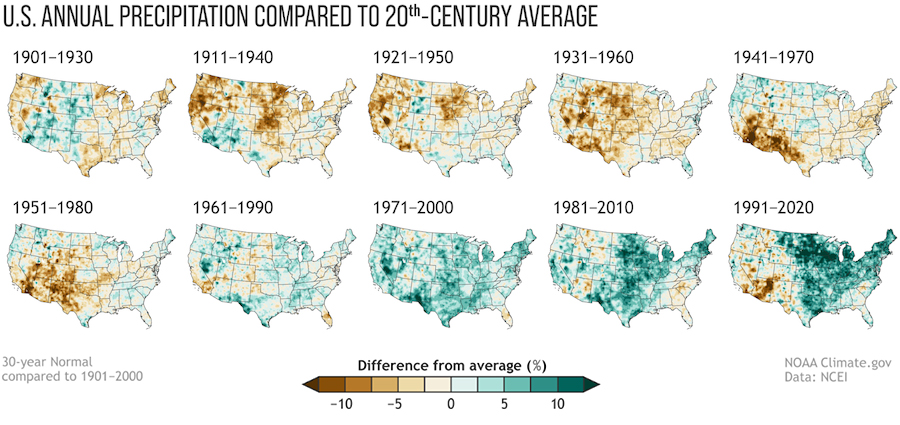

Traditional drought assessment methods based on assumptions of a stationary climate may underestimate current and future drought risks, thereby posing challenges to agricultural producers, water managers, businesses, and decision-makers in planning and allocating resources effectively. For example, the Southwest U.S. is not seeing a strong trend in annual precipitation over the full period of record (1895–2023), but rising temperatures and evaporation have led to more rapidly depleted soil moisture, runoff, and streamflow in an already arid region. As a result, droughts feature higher temperatures than past droughts and are more impactful on the hydrology of the region, which is already stressed by human use. On the other hand, the Midwest and Northeast U.S. are trending wetter, with more precipitation falling as rain and less as snow.

Drought assessment processes and tools need to improve such that they consistently and deliberately consider many factors in accounting for periods of record, drought type, impacts, regionality, and seasonality. In a non-stationary climate, changes in how we assess drought could impact disaster relief, improve adaptation programs, and inform future policy.

In addition to describing how a changing climate is impacting drought assessment, the report identifies priority actions and research questions organized around 15 focus areas. The areas of research and action discussed include:

- Improved understanding of how drought indicators relate to potential future impacts on the ground

- Improved descriptions of how non-stationarity should shape our expectation for future water demands and drought frequency, intensity, and duration

- Improved understanding of the utility and application of drought assessments for decision-makers as they manage drought risks

- A holistic view of drought risk that combines physical information about water resources with an understanding of different communities’ exposure and vulnerability.

The report was developed as part of a Drought Assessment in a Changing Climate Technical Working Meeting co-hosted by NIDIS and the USDA Climate Hubs and held in Boulder, Colorado, on February 28–March 1, 2023. The report offers a rich collection of ideas for action and research that federal, tribal, state, local agencies, and academic institutions can advance.

Learn more on the report web page.