From Dust to Deluge: Weather Whiplash Devastates Texas

The Land of Droughts to Flooding Rains

Weather whiplash is the abrupt and intense change from one extreme weather condition to another, such as dramatic temperature swings from hot to cold, heavy snowfall to rapid melt, and, as is common in Texas, a period of prolonged drought followed by flooding. In recent years, weather whiplash events have been observed across the United States. Examples include the 2013 flood in Colorado that ended a local drought. In fall 2024, Oklahoma had its 10th driest October on record followed by the wettest November which led to flooding. Also in 2024, wildfires scarred the drought-stricken landscape around Ruidoso, New Mexico; then heavy rainfall in 2025 fell on the dry and scarred landscape, causing flash flooding and devastating the community.

Weather whiplash events are more common in some parts of the United States than others. In central Texas, the Concho Valley, Big Country, and Hill Country regions (referred to as the Edwards Plateau region) are more prone to these events due to the combination of their geographical location, geology, and climate. Due to their location, it is common for warm, moist air from the Gulf of America to collide with cooler air from the Great Plains or Pacific Ocean. When this occurs, the warm, moist air is forced upward, causing the moisture to condense and form thunderstorms. This upward movement is hastened by the Balcones Escarpment, a fault line defined by a sudden increase in elevation onto the Edwards Plateau region. This part of Texas is defined by steep canyons, shallow soils, and exposed limestone and granite, which are very conducive to rapidly generating runoff and, therefore, flash flooding. The Edwards Plateau region has a lower annual precipitation compared to other parts of the state, and the sudden transition from droughts to flooding rains is a familiar occurrence.

Weather Whiplash Devastates Texas in 2025

Texas experienced a significant weather whiplash event in July 2025. The Edwards Plateau region has been in long-term drought since late 2021. This included a total of 180 weeks with Severe Drought (D2) or worse and 105 weeks with Exceptional Drought (D4) somewhere in the region, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. D4 is the most intense category of drought and often associated with long-term drought conditions. By the end of May 2025, long-term drought indicators, including reservoir and groundwater levels, were showing exceptionally poor condition. Then, in June and July, the region experienced historic and devastating floods.

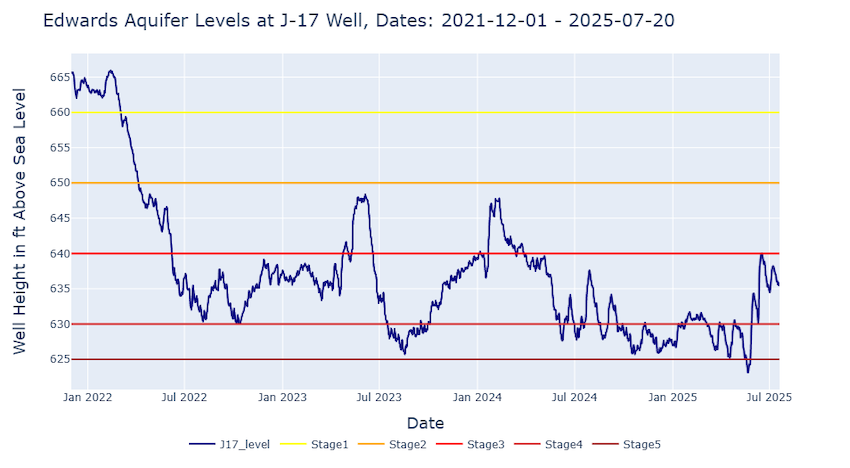

Before the flooding event, Canyon Lake, a reservoir on the Guadalupe River, was at 46% of total reservoir capacity. Medina Lake was just above 2% full, and the Edwards Aquifer dropped below the Stage 5 drought threshold, the most extreme threshold, for the first time since the Edwards Aquifer Authority’s inception in 1993. Other impacts of the multi-year drought in central Texas include wells running dry and water restrictions across the Edwards Plateau. Popular recreational sites like Jacobs Well and the Blue Hole had to close due to low water. Beginning in 2022, ranching operations were impacted by lack of water and forage, and cattle producers were forced to sell cattle due to high costs of hay, supplemental feed, and lack of water.

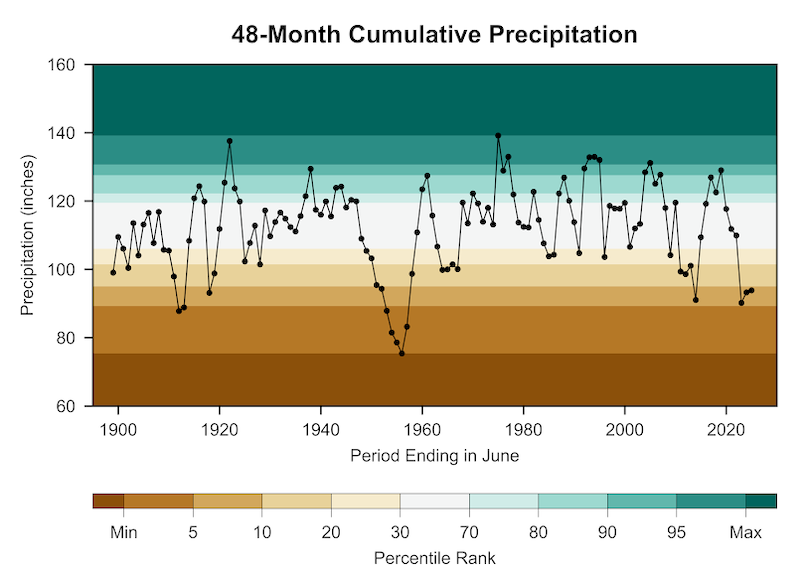

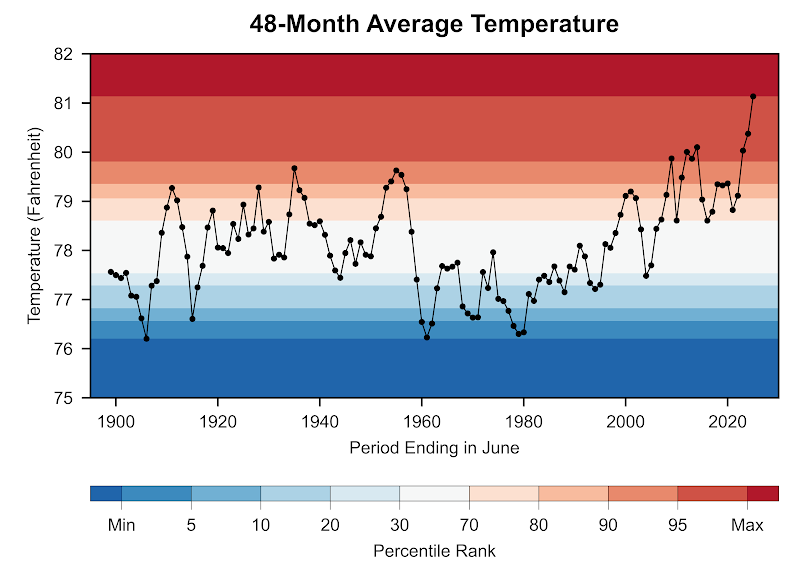

Figures 1 and 2 highlight the long-term dryness and persistent heat of the current drought. Each point in these figures shows the 48 months leading up to June in each year. Figure 1 shows that the 4 years (48 months) ending in June 2023 experienced the third-lowest 4-year precipitation accumulation since records began (2024 and 2025 were also very low). Similarly, Figure 2 shows the 4 years leading up to June 2025, marking the hottest 4-year period on record. Together, these figures highlight the fact that while the lack of precipitation is comparable to previous droughts, the region has never experienced a drought as hot as the present one.

Long-Term Dryness Has Impacted the Edwards Plateau Region in Recent Years

The Current Long-Term Drought Has Been Characterized by Hotter Temperatures

The first signs of relief from long-term drought occurred in April and May 2025. Precipitation totals during both months were near average, the first back-to-back months of average to above-average precipitation since September-October 2023. By early June 2025, the drought in central Texas was beginning to show signs of improvement, including increased upper-layer soil moisture, improved pasture conditions, and increased greenness across the region.

Deluges in June and July 2025 followed average and above-average precipitation in April and May. A flash flood hit San Antonio on June 12, taking 13 lives and causing substantial damage. Following these floods, the J-17 well, an index well used to monitor the Edwards Aquifer's San Antonio Pool, rose from below 625 feet (stage 5 drought restrictions) to around 635 feet (within stage 3 drought restrictions; refer to Figure 3). These floods caused little to no change in the reservoir levels. Overall, June precipitation was not enough to improve the exceptionally poor hydrologic drought conditions.

Despite Recent Flash Flooding Events, Water Restrictions Remain Due to Long-Term Drought

In early July, the Edwards Plateau region was hit with intense heavy rainfall that led to flash flooding (Figure 4). The convergence of two atmospheric systems led to torrential rainfall during July 3-5, 2025. One of these systems was ex-Tropical Storm Barry. As the remnants of this tropical system moved north, it slowed and combined with another low-pressure system that moved east from the Pacific Ocean. This convergence enabled slow-moving convective storms to dump torrential rains over central Texas on July 4, 2025, tragically devastating the region and leading to the loss of lives.

Torrential Rains Flood the Edwards Plateau

Is This How Drought Ends in Central Texas?

When looking at the three previous most prolonged and impactful drought events for central Texas (1917-1919, 1950s, 2011-2015), all events ended with a major flood. However, it is important to note that not all flood events end droughts, and not all droughts have ended in floods, but the three most severe, multi-year drought events ended with periods of multiple flood events in the State of Texas.

1917-1919 Drought

With an annual total of only 10.04 inches, 1917 holds the record for the driest calendar year for the Edwards Plateau climate division. Rainfall in 1918 was also below average and, while not a record, was still low enough to prolong the drought. The drought finally ended in 1919, which holds the record for the wettest year for the Edwards Plateau region, with an annual total of 41.56 inches. The remnants of a major hurricane accounted for a majority of the rainfall that year. The Hurricane of 1919 (sometimes also called the “Florida Keys Hurricane”) made landfall as a Category 3 storm near Corpus Christi on September 14, 1919. Heavy rainfall from this storm caused flooding along the lower Colorado, Guadalupe, and Nueces Rivers, as the state experienced weather whiplash.

1950s Drought

The drought of the 1950s lasted from 1951- 1957. There were at least two flood events within this period (September 1952 in the Colorado and Guadalupe River basins, and June 1954 when Hurricane Alice flooded the Pecos and Devils Rivers), but these floods were so localized that they did little to alleviate the statewide drought. According to the Texas State Library Archives, after 7 years of a devastating and costly drought, rain fell again beginning on April 24, 1957—a date later known as “The Day of the Big Cloud.” The storm dumped 10 inches of rain within a few hours, accompanied by destructive hail and multiple tornadoes. Continuous rain for the next 32 days led to flooding that killed 22 people and forced thousands from their homes. It is reported that every major river in Texas flooded. Damages included washed out bridges and homes that were completely swept off their foundations. The environment had gone from one extreme to the other.

2011-2015 Drought

The 2011-2015 drought ended with the wettest May on record in Texas. A flooding outbreak occurred when a tropical system brought torrential rains and tornadoes from Oklahoma through central Texas on May 24-26, 2015. This included a roughly 35-foot rise on the Blanco River near Wimberley, Texas. With the landscape drying out again, the Texas Hill Country was hit by another flood event as ex-Hurricane Patricia moved over the region on October 23. 2015 would become the wettest year on record for the state of Texas.

2021-2025 Drought

What about the 2021-2025 drought? So far, the flooding of early July 2025 was not enough to end the ongoing drought in the Edwards Plateau region. Continued rainfall in the region is still needed to raise the still-low reservoirs and recharge the Edwards Aquifer to above-drought stages.

Nor does it seem that the drought made the floods worse, although more research is needed to understand the exact contribution of the drought to the flood. Analysis by John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas State Climatologist, shows that “the drought in the Hill Country was exclusively long-term drought, reflected in streamflow, reservoir levels, and aquifer levels. During the month or two prior to the flooding, rainfall in the area was near or somewhat above normal, so the shallow soils in the area would not have been unusually dry.”

Drought and Flash Flood Early Warning

Drought and floods are the extreme ends of a shared spectrum. When too much of a region's annual precipitation comes too fast, flash flooding is possible. Subsequently, if too little precipitation falls, the onset of drought can occur. Better understanding of how long-term drought conditions impact communities’ vulnerability to devastating flash floods can help provide early warning of the sequential, compounding, and cascading effects of hydrological extremes.

Research needed to inform this work includes the relationship between the drought conditions and the rate of runoff and soil infiltration, the ecological response to rapid changes, and the impacts of prolonged drought on the local and regional vulnerability to severe storms. Scientists at NOAA are working to address the complex interplay between these factors that connect extremely dry to extremely wet conditions, as well as the significant regional dependencies of such environmental relationships. Advancements in NOAA science will help to inform community preparedness for droughts and flooding.

Authors

Jason Gerlich and Joel Lisonbee

Regional Drought Information Coordinators at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES)/National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS)

Andy Hoell and Kelly Mahoney

Research Meteorologists with the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory

Adam Lang

Communications Coordinator at CIRES, NOAA/NIDIS