New NOAA Report: Exceptional Southwest Drought Exacerbated by Human-Caused Warming

Since early 2020, the Southwest United States has suffered record low precipitation and near-record high temperatures, gripping the region with an unyielding, unprecedented, and costly drought. This exceptional drought—marked by massive water shortages, destructive wildfires, emergency declarations, and the first ever water delivery shortfall among the states sharing the Colorado River—punctuates a two-decade warm and dry period that has baked the Southwest.

A newly released report from the NOAA Drought Task Force, which is a collaboration between the NOAA Climate Program Office, National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS), and leading scientists, addressed four critical questions about the 2020–2021 Southwestern U.S. drought:

- How bad is this drought?

- What caused it?

- When will it end?

- And, what does the future hold?

According to the report, a natural but severe period of low rain and snowfall and warm temperatures exacerbated by human-caused global warming were the main drivers of this extreme drought. The drought caused roughly $11.4–$23 billion in economic losses in 2020—including impacts from associated wildfires. Economic losses for 2021 will also be substantial, and the drought is expected to continue at least into next year.

“Severe droughts relative to our current climate are projected to occur more often in the Southwest United States," said co-author Andy Hoell with the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory. "Continued warming will reduce soil moisture and the amount of water that flows into rivers and reservoirs, impacting the water supplies that 60 million people depend on."

This report can help inform and prepare decision makers and the public for the continuing drought and future droughts like this one, which has occurred amidst the Southwest region growing increasingly arid.

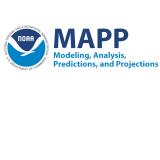

Swift and Severe Consequences

The Southwest—encompassing Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah—experienced successive dry and warm winter seasons in 2020 and 2021, along with a failed 2020 summer monsoon. Over the 20 months from January 2020 to August 2021, the Southwest had its lowest precipitation totals on record (since at least 1895), as well as the third-highest daily average temperatures (Figure 1). Together, exceptionally low precipitation and warm temperatures reduced mountain snowpack and increased evaporation of soil moisture, leading to persistent and widespread drought over the last 20 months.

The environmental, social, political, and economic consequences of this drought have been swift and severe. The 2020 wildfire season burned over 10 million acres, about three times the burning area typical during 2001–2018. Many surface water reservoirs across the Southwest, which are designed to buffer periods of drought, have dropped to historic lows: 57% of average Spring capacity. This led to electricity blackouts amidst record-setting heat waves as electricity demand from air conditioning peaked.

Climate Change-Fueled Heat, Record Low Rain

The collective expertise of the Drought Task Force found that the 2020–21 Southwestern drought was caused by a combination of successive seasons of low precipitation (most likely due to natural variations in climate) and natural and human-caused warming. The warming has accelerated snowpack losses and drawn water from the land surface more rapidly than in previous years.

The low precipitation across U.S. states and seasons appears to have been largely due to natural, but unfavorable, variations in the atmosphere and ocean. Meanwhile, exceptionally warm temperatures caused both a shortened snow season and increased atmospheric thirst for moisture from the land, drying it out. While low precipitation and resulting dry soils likely contributed to these above-normal temperatures, the Drought Task Force report concludes that the incredibly warm temperatures the Southwest experienced in 2020 and 2021 far exceeded those that can be explained by random variations in climate alone. Human-caused warming played a major role.

A Harbinger of a More Arid Future

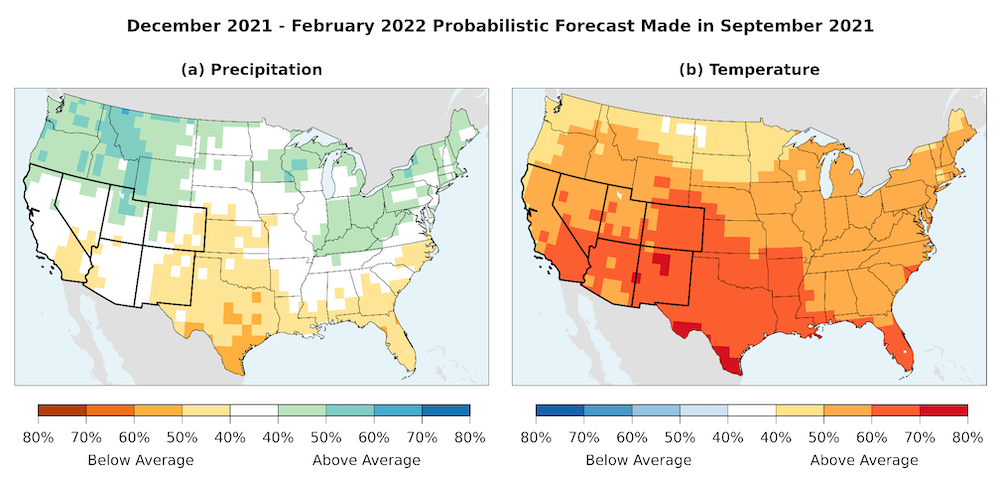

While summer 2021 brought welcome monsoon rains to parts of the Southwest, several seasons (or years) of above-average rain and high elevation snow are needed to refill the rivers, soils, and reservoirs that more than 60 million people depend on for their water, livelihoods, food, power, and recreation. This deficit, when combined with the La Niña forecast for the coming winter, suggests that the current drought will last well into 2022 for parts of the Southwest, potentially longer (Figure 2).

This extraordinary drought occurs in the context of the Southwest United States becoming increasingly arid in the longer-term; the region is arguably in the midst of a two-decade-long “megadrought.” With continued warming, the atmospheric demand for soil moisture will continue to increase, making even randomly-occurring low or near-normal precipitation years a potential drought trigger. While 2020–21 was an exceptional period of low precipitation, the drought that has emerged is a harbinger of a future that the more arid Southwest must take steps to manage now.

This NOAA Drought Task Force report was the result of research funded by NIDIS through the NOAA Climate Program Office’s Modeling, Analysis, Predictions and Projections (MAPP) Program. The Drought Task Force aims to advance the understanding of drought causes and predictability, as well as drought modeling, prediction, and monitoring capabilities, building on decades of preceding research on drought, hydroclimate, and related modeling. The Drought Task Force IV leads and report authors are:

- Justin Mankin (Co-Lead), Dartmouth College

- Andrew Hoell (Co-Lead), NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory

- Isla Simpson (Co-Lead), National Center for Atmospheric Research

- Rong Fu (Co-Lead), University of California Los Angeles

Read the full report, or learn more about the Drought Task Force and other NIDIS-supported research.