NIDIS Summit Connects Drought and Public Health

Over the last century, droughts have caused more deaths internationally than any other weather- or climate-related disaster. Droughts in the United States, however, are generally not thought of as public health threats. The National Drought and Public Health Summit, held June 17‒19, 2019 in Atlanta, brought together a diverse set of local, state, federal, tribal, non-profit, and academic stakeholders for a discussion around the linkages between droughts and human health. The goal was to discuss ways to properly prepare our nation’s public health agencies and organizations for the health hazards associated with drought, which, in turn, can reduce negative outcomes and save lives.

Dr. Jesse Bell with the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Public Health and summit co-host, opened with a discussion on the disconnect in our current understanding of the relationship between drought and public health. Bell noted that although steps can be taken to prevent negative health outcomes associated with drought, existing surveillance is not designed to identify health outcomes when drought actually occurs.

Dr. Jesse Bell with the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Public Health and summit co-host, opened with a discussion on the disconnect in our current understanding of the relationship between drought and public health. Bell noted that although steps can be taken to prevent negative health outcomes associated with drought, existing surveillance is not designed to identify health outcomes when drought actually occurs.

Many of the presentations that followed discussed known or potential human health outcomes related to drought, including:

- Droughts increase the probability of high arsenic concentrations in private wells and population exposed to arsenic across the contiguous United States (Melissa Lombard, USGS).

- A 2017 study found a 1.55% increase in mortality from high severity worsening drought (Jesse Berman, University of Minnesota).

- There is a relationship between drought and wildfire episodes and an association between wildfire smoke and adverse health outcomes. (Ambarish Vaidyanathan, CDC).

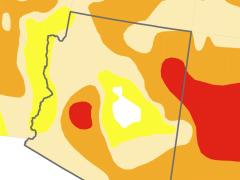

- The frequency of dust storms, often associated with drought, more than doubled from the 1990s and 2000s in the Southwest. Rising dust can cause negative effects on human health, such as increased traffic accidents and Valley Fever (Daniel Tong, GMU/NOAA).

- Drought accounted for 38% of West Nile virus cases in Nebraska between 2002‒2018. (Kelly Helm Smith, National Drought Mitigation Center).

- Drought will likely create new areas that could support Valley Fever (coccidioidomycosis), but may make some historic areas too dry (Orion McCotter, CDC).

- Internationally, drought can lead to reduced food intake, lack of a varied diet, the spread of disease, and forced migration (Sally Edwards, Pan American Health Organization).

Another important topic discussed at the meeting was not just how drought impacts human health, but what populations will most be affected by drought. Presenters identified vulnerable populations, both nationally and internationally, and ways to reach them.

The meeting also helped to better identify how various partners and stakeholders attending, along with other agencies, can incorporate public health impacts into drought and climate tools, and vice versa, prepare the public health community for drought.

The summit ended by discussing next steps, including the role of NIDIS. A few of the potential follow-up items included researching the costs of drought-related health effects, linking drought indices to public health, convening regional drought-public health meetings, and many more. The Summit presentations will be available for viewing soon.

A final report will also be prepared to highlight the topics discussed, key findings, and next steps. View the meeting agenda and presentations.

Thank you to the Summit partners:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

NOAA National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS)

University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Public Health

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)

National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC)

Robert B. Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute at the University of Nebraska