Southern Plains Drought Assessment 2020-2025

In March 2020, Moderate to Severe Drought (D1-D2) intensified rapidly to Exceptional Drought (D4) along the lower Rio Grande in Texas, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Over the next five years, drought severity waxed and waned across the Southern Plains, shifting location and extent but never leaving the region. Drought touched the lives of nearly every resident of the region.

NOAA's National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS), in partnership with the Southern Regional Climate Center (SRCC), conducted a post-drought assessment of the Southern Plains drought of 2020-2025 to understand the drought’s evolution and impacts (including economic costs) and communicate them to decision-makers across the region, the private sector, and the public. NIDIS is an interagency program within the Climate Program Office, which is part of NOAA's Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research.

Drought assessments are crucial to build resilience to drought. They can inform future drought risk management and mitigation actions by analyzing drought hazard and exposure, impacts, and responses. Through documenting and, where possible, quantifying the impacts of drought events, and response actions taken, assessments can share best practices and local insights to prepare for future droughts

Purpose and Scope

This executive summary presents the key findings of NOAA Technical Report OAR-NIDIS-007, Southern Plains Drought Assessment 2020-2025. The Southern Plains Drought Early Warning System (DEWS), for the purposes of this document, primarily encompasses Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas, with consideration of impacts on adjacent states: eastern New Mexico, western Louisiana, and Arkansas. This assessment was produced as a partnership between NIDIS and SRCC in support of the NIDIS Reauthorization Act of 2018 (Public Law No: 115-423). It examines the drought's development, progression, impacts to multiple sectors, and forecast model performance. The overarching goal of this document is to inform drought resilience and improve preparedness strategies for future events.

The first drought period examined in this assessment began on June 16, 2020 and ended nearly a year later, on June 8, 2021. The second drought period began on October 26, 2021, and ended on June 8, 2025. With only four months between these two drought events and the impacts of the first still lingering when the second began, these events were combined within this assessment.

While the drought examined in this study ended on June 8, 2025, drought is reforming across the region at the time of this report publication (November 2025). La Niña, which formed in October 2025, is likely one cause of drought’s return to the region. This is the fifth La Niña to impact the Southern Plains in the last six years.

Key Takeaways

A Complex, Multi-Year Event

The 2020-2025 drought was characterized by periods of rapid intensification, often referred to as "flash drought," and periods of partial recovery. This fluctuating severity presented unique challenges for resource management.

Substantial Costs to Agriculture

The agriculture sector experienced significant negative impacts, including widespread crop failures, particularly winter wheat and cotton; diminished range and pasture quality, necessitating supplemental livestock feeding; and reduced livestock herd sizes. NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) estimated the economic impact of the drought from 2020-2024 exceeded $23 billion.

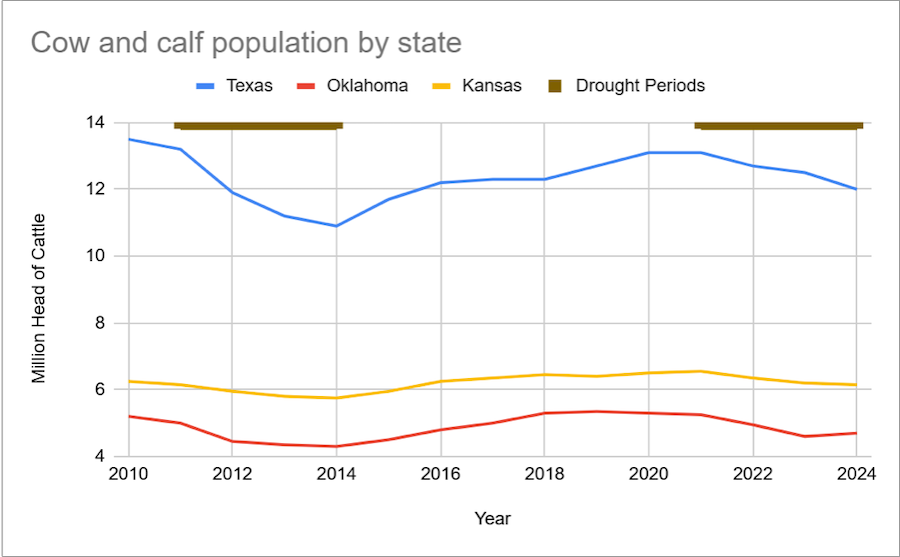

Reduced Herd Numbers

In times of drought, ranchers adapt to lack of feed or pasture by thinning their herds or moving their cattle and calves to another state. For example, the 2011 drought in the region drove a decline in the Texas herd from 13.3 million in 2011 to 11.1 million in 2014. One of the reasons the 2020-2025 drought was so impactful is that parts of the region had not fully recovered from the 2010-2015 drought. Texas’s herd size increased back to 13.1 million by 2020, but then declined to 12.0 million in 2024. Oklahoma's herd size declined from 5.3 million in 2020 to 4.7 million in 2024. The Kansas herd declined from 6.5 million in 2020 to 6.15 million in 2024 (USDA's National Agricultural Statistics Service).

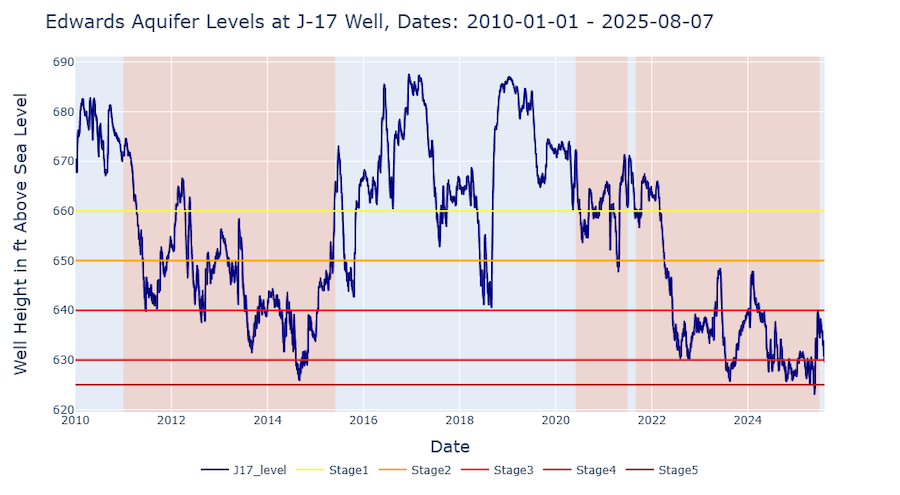

Significant Water Resource Stress

The droughts in 2010-2014 and 2020-2025 left Falcon International Reservoir, Elephant Butte Reservoir, Canyon Lake, the Edwards Aquifer, and other water sources near record-low levels. The storms in summer 2025 only improved the conditions of these water sources for a short time. The Barton Springs-Edwards Aquifer Conservation District recently declared Stage 3 Exceptional Drought, effective October 1, 2025. This marked only the second time in the District’s 38-year history that an Exceptional Drought was declared, with the first occurrence in December 2023.

Wildfire and Other Notable Ecological Consequences

The drought contributed to increased wildfire activity—including the largest wildfires in both Texas and Louisiana state history—and stressed riparian and aquatic ecosystems.

Actions Can Be Taken to Build Resilience to Drought

Optimizing mesonet data, diversifying water sources, implementing efficient irrigation techniques, and educating producers on the link between the U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Livestock Forage Disaster Program are some of the steps that can be taken in the Southern Plains to build resiliency and mitigate risk.

Background

The Southern Plains region is historically prone to drought. Notable past events include the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, the 1950s drought (the drought of record for many areas), and the intense 2010-2015 drought. The region experiences large swings in seasonal precipitation from year to year, making it highly susceptible to more severe drought conditions. Moisture from the Gulf of America brings more precipitation to the eastern plains in a typical year than can evaporate, while in western plains—farther from the Gulf—the opposite is true.

Texas, in particular, sits at the same latitude as the Saharan Desert. The influence of the sub-tropical ridge, a high-pressure system characterized by sinking air, delivers long dry spells through the summer months. The Southern Plains can also experience intense deluges as tropical systems move north from the Gulf. This means the region often swings back and forth between plenty of water and not enough water.

Causes

La Niña was likely the primary driver of persistent dry conditions in the Southern Plains for the first three years (i.e., triple-dip La Niña). The absence of the La Niña pattern in 2024 could explain the brief reprieve in drought conditions during that year, but drought did not disappear completely, showing that other factors were at play. One such factor, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), was in a cool phase during 2020-2025. A cool PDO pattern amplifies the influence of La Niña on precipitation patterns across the southern U.S. Long-term climate trends, including increased temperatures, also played a significant role.

La Niña, and the characteristic drought in the Southern Plains, returned in late 2024 into 2025. While conditions improved in summer 2025, the fifth La Niña winter in six years formed in October 2025, potentially causing drought to expand across the region again.

Impacts

Agriculture

- The agriculture sector experienced significant negative impacts: widespread crop failures, particularly winter wheat and cotton; diminished range and pasture quality, necessitating supplemental livestock feeding; and, in many cases, herd reductions. It is estimated that the economic impact of the drought in the Southern Plains from 2020-2024 exceeded $23 billion.

- Texas had a greater percentage of failed crops than Kansas and Oklahoma in 2022, the peak year of the drought. In Texas, this included 25% abandonment for corn, 45% for soybeans, and 74% for cotton. The cotton crop in Texas would have been valued at around $2.4 billion in 2022 with normal growing conditions, but with the 74% abandonment rate for cotton (assuming stable market prices), the cotton crop in Texas in 2022 was valued around $640 million.

- In times of drought, ranchers adapt to lack of feed or pasture by thinning their herds. One of the reasons the 2020-2025 drought was so impactful is that parts of the region had not fully recovered from the 2010-2015 drought. The 2011 drought drove a decline in the Texas herd from 13.3 million in 2011 to 11.1 million in 2014. The Texas cow/calf population never fully recovered and was at 13.1 million in 2020. Texas’s herd population again fell with the 2020-2025 drought, with a herd population of 12.0 million in 2024. Oklahoma's herd size declined from 5.3 million in 2020 to 4.7 million in 2024. The Kansas herd declined from 6.5 million in 2020 to 6.15 million in 2024 (USDA's National Agricultural Statistics Service).

Water Supply

- Several long-term stream gauges recorded record low flows, impacting aquatic ecosystems and water availability.

- Groundwater resources were impacted substantially by the 2020-25 drought in the Southern Plains. Over the course of the drought, analysis of well data showed that 131 wells showed a minor decline (net decrease of 0% to 10%) and 48 wells saw a major decline (greater than 10% net decrease) in groundwater levels.

- In May 2025, the Edwards Aquifer Reached Stage 5 Water Restrictions (See Figure ES.2) for the first time since the creation of the Edwards Aquifer Authority in 1993.

- Falcon International Reservoir reached a minimum of 8% of capacity in October 2023, similar levels to those seen during the 1956 drought. This jeopardized water supplies in the lower Rio Grande Valley.

- Elephant Butte Reservoir was at 3.8% of capacity in August 2022, impacting regional irrigation and increasing water salinity along the Rio Grande. Levels remain critically low (4% full) as of October 30, 2025.

- Canyon Lake dropped below 55% of capacity in September 2024, the lowest level since it was first filled in the late 1960s. Canyon Lake continued to fall through the end of 2024, driven by prolonged drought and increased regional population demands.

Ecological

- Dry conditions and abundant fuel loads contributed to several large wildfires, including the Smokehouse Creek Fire, the largest in Texas history (February 26–March 16, 2024), and the Tiger Island Fire, the largest in Louisiana history (August 22–October 25, 2023) (Inciweb).

- Reduced streamflow harmed riparian ecosystems, affecting biodiversity, specifically in the Lower Colorado River.

- Drought conditions stressed vegetation, affecting grazing lands and wildlife habitat. In many cases, this led to fuel for wildfires such as those seen in East Texas during fall 2023.

Building Resilience in the Southern Plains

Based on the findings of the technical report, several key priority areas emerged that could support the region in building greater drought resilience:

Enhance Drought Monitoring for Early Warning

High-quality, real-time in situ weather observations for drought early warning are crucial, even when forecasts are available. Mesonets are vital to provide high-frequency in situ data that capture temperature, wind, soil moisture, precipitation, and more. Recently completed research supported by NIDIS developed a method to optimize mesonet data and found a machine learning model more than doubled the accuracy of shallow soil moisture measurements nationally. The accuracy of the new model increased in response to an increasing number of stations, demonstrating the clear advantage of increasing station coverage in regions with limited in situ data collection. This suggests a direct return on investment from mesonet expansion.

Improve Seasonal Forecast Capability

La Niña conditions emerged in early fall 2020. Typically, La Niña conditions in fall and winter result in above-average temperatures and below-normal rainfall for the Southern Plains. Overall, the 2020-2025 drought coincided with three consecutive La Niña events (commonly termed the “triple-dip La Niña”), except for the El Niño event in 2023-2024. The absence of the La Niña pattern in 2024 could explain the brief reprieve in drought conditions during that year, but drought did not disappear completely, meaning other factors were at play. Further research is needed to enhance the accuracy of physics-based seasonal forecast models at longer lead times and to determine the intrinsic predictability of drought on a seasonal time scale.

Develop Comprehensive Drought Plans

Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas have developed comprehensive water plans and innovative drought monitoring and response approaches tailored to their specific needs. To improve drought resilience, cities, and counties, as well as other drought-vulnerable communities, that do not have drought plans in place should consider creating one in preparation for the next drought.

Promote Water Conservation

Water conservation, through efficient irrigation techniques, rainwater harvesting, and public awareness campaigns, can stretch limited water supplies during dry periods. Cooperative Extension programs in Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas conduct research, share information, and hold regular trainings on efficient irrigation techniques.

Diversify Water Sources

In tandem with water conservation and improved drought plans, interviews with regional landholders for this report identified the vulnerability of relying on a single water source. Communities are increasingly exploring alternative water sources like groundwater, reclaimed water, and desalination.

Collect Drought Impacts

Though satellite data and climate models provide essential insight, they cannot fully capture the lived experiences of people affected by drought. Tools like CMOR (Condition Monitoring Observer Reports) and CoCoRaHS (Community Collaborative Rain, Hail & Snow Network) are standout examples of public impact-reporting systems that offer timely, hyperlocal data. Incorporating impact data can ensure drought plans address sectors exposed to drought impacts in the past, target water conservation practices based on past low water levels, and diversify water sources for producers and communities.

Educate Stakeholders on the USDM and USDA Disaster Recovery Programs

Future activities in the Southern Plains region could include partnering with state climate offices, the USDA Farm Service Agency, and the National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC) to provide tutorials and webinars to demonstrate how local stakeholders can get involved in the USDM process and apply for relief through USDA programs, such as the Livestock Forage Disaster Program.

Address Future Drought

In the High Plains (including the western edge of the Southern Plains), long-term trends show increasing temperatures and evapotranspiration, which will further strain limited water resources. Incorporating future projections into water management decision-making is essential for long-term planning. Investing in drought-resistant crops and infrastructure represents a step towards building resilience in the face of potentially more frequent, rapid, and severe droughts.

Conclusion

NOAA’s NCEI estimated that the economic impact of the drought on agriculture in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas from 2020-2024 exceeded $23 billion. The prolonged drought depleted water resources, stressed ecosystems, and caused economic hardship for farmers and ranchers. This drought was particularly impactful because parts of the region had not fully recovered from the 2010-2015 drought. In some parts of the region, such as southern Texas, the drought hasn't ended even as this report is being written—and neither should the conversation about this ongoing drought. La Niña developed once again in October 2025, potentially causing drought conditions to develop and worsen.

This report provides an initial assessment of the 2020-2025 Southern Plains drought. Opportunities identified in this report, such as enhancing drought monitoring, diversifying water supplies, and conserving water through efficient irrigation, are key steps to advancing drought resilience. NIDIS and SRCC will continue to work with stakeholders in the region to advance these priority areas as well as monitor and communicate drought conditions, outlooks, and impacts.

For more information, read the drought assessment or contact Joel Lisonbee (joel.lisonbee@noaa.gov).