A Series of Atmospheric Rivers Have Hit Parts of the West. What Does This Mean for Drought?

Key Points

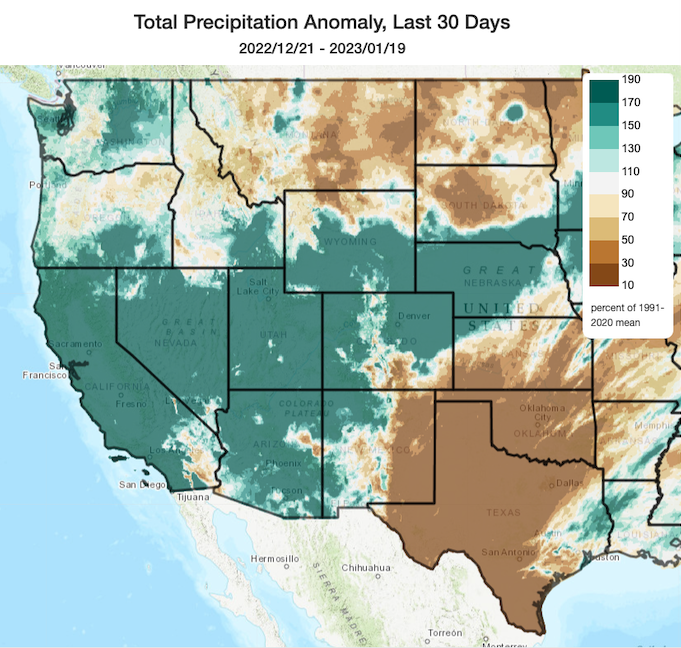

- Starting on December 26, 2022, a series of 9 atmospheric rivers (ARs) brought significant amounts of rain, snow, and wind to California and other parts of the western United States over a 3-week period.

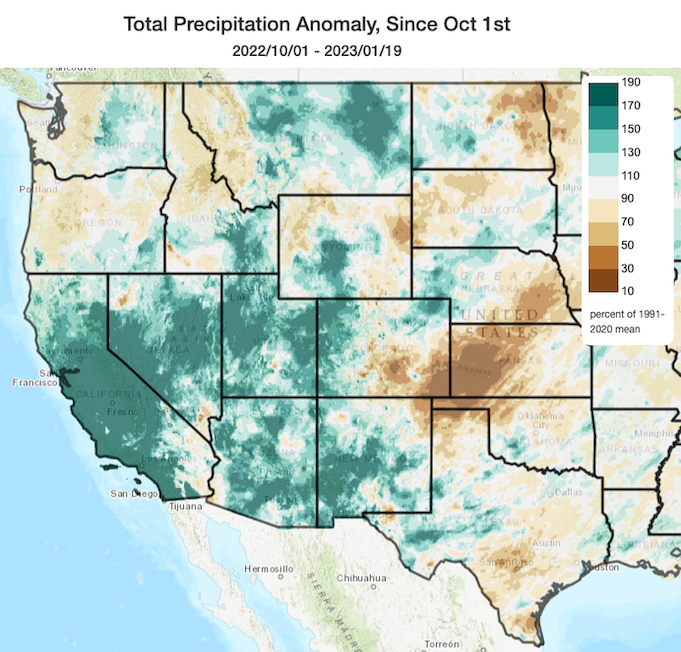

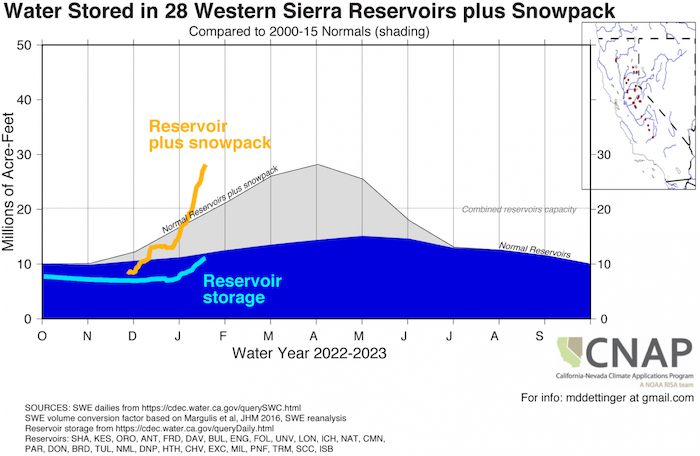

- 80% of a full seasonal snowpack was deposited in California during these storms. Statewide, precipitation over these 3 weeks was 11.2 inches, which is 46% of a full water year.

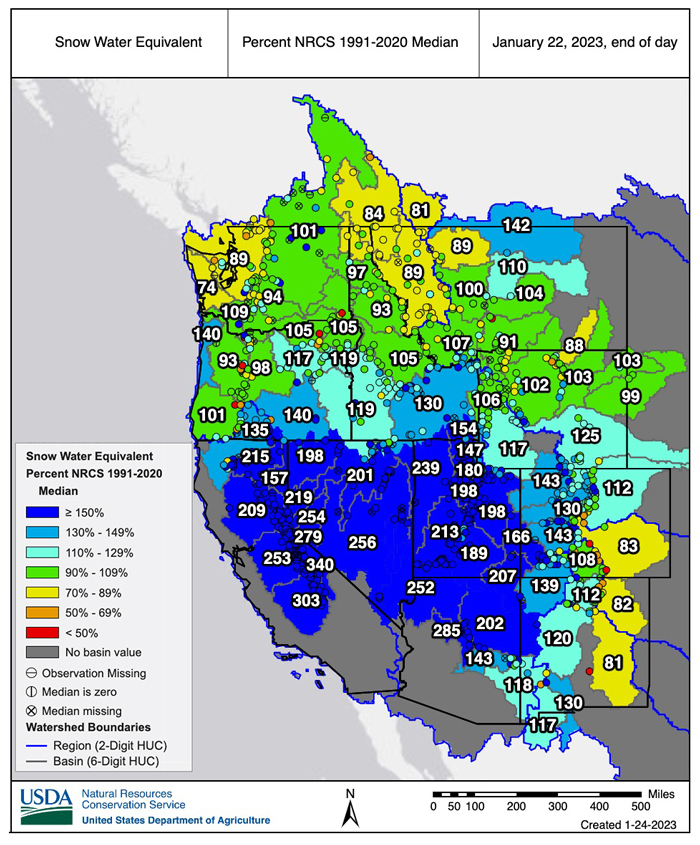

- The AR events have been a big boost to mountain snowpack across the West, where snow water equivalent (SWE) totals are well above normal for this time of year except for many parts of the Cascades and the Northern Rockies, where accumulation has slowed since the beginning of January.

- Given that it is still early in the snow accumulation season, water year totals could either be moderate if the rest of the winter and spring are dry, or relatively high if precipitation continues.

- According to Natural Resources Conservation Service SNOTEL, as of end of day January 22, 2023, the snow water equivalent for the California Region is 215%, the Great Basin is 206%, and the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins are 146% and 218%, respectively.

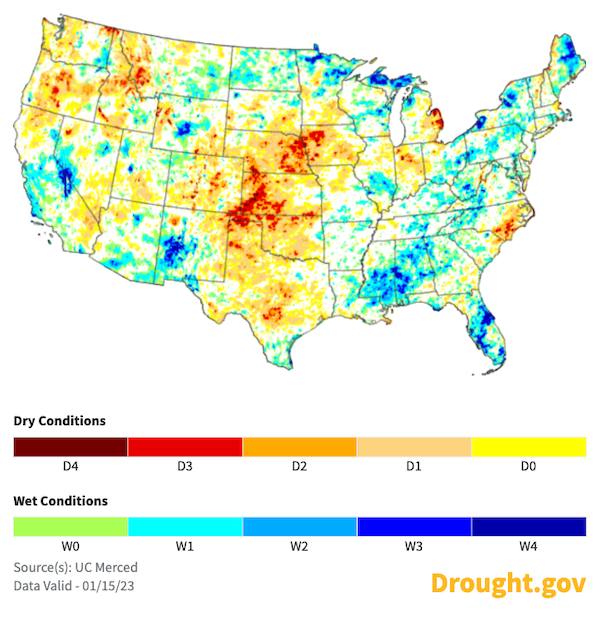

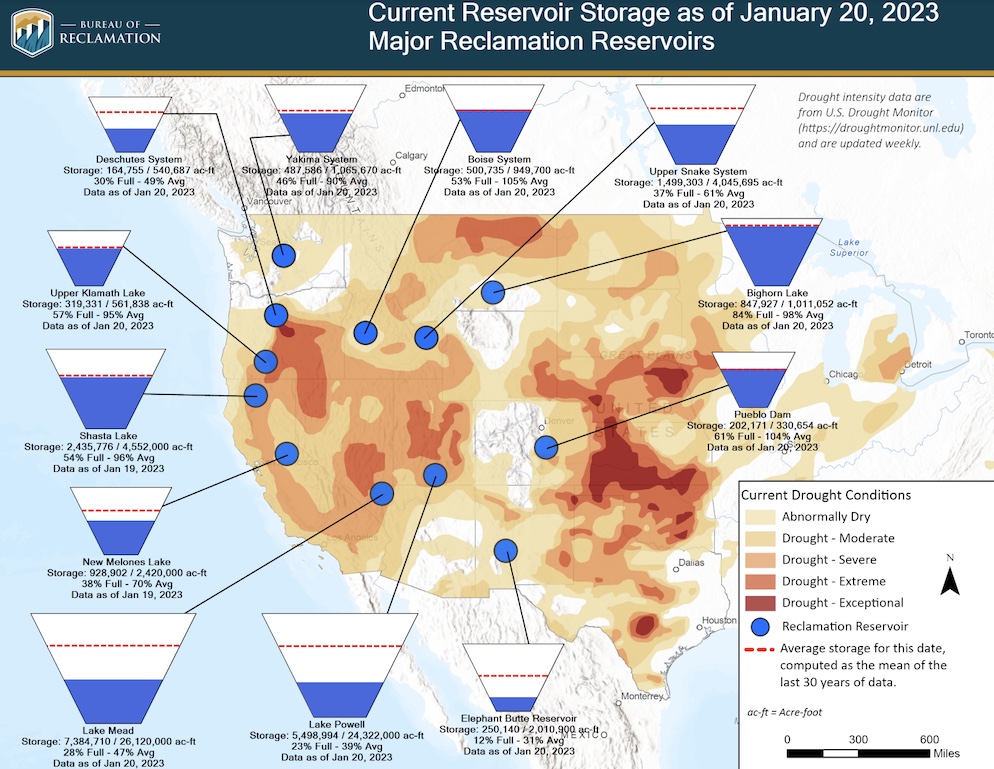

- These recent storms improved drought conditions by increasing soil moisture throughout much of the West, especially in California. The amount of water stored in many reservoirs increased, but some are still well below historical averages for this time of year.

- Despite the drought improvements in many areas, long-term drought persists in parts of the West. Reservoir storage deficits, such as those within the Colorado River system, and groundwater and soil moisture deficits (especially in the Northwest) that have built up over many months to years will require additional precipitation to overcome.

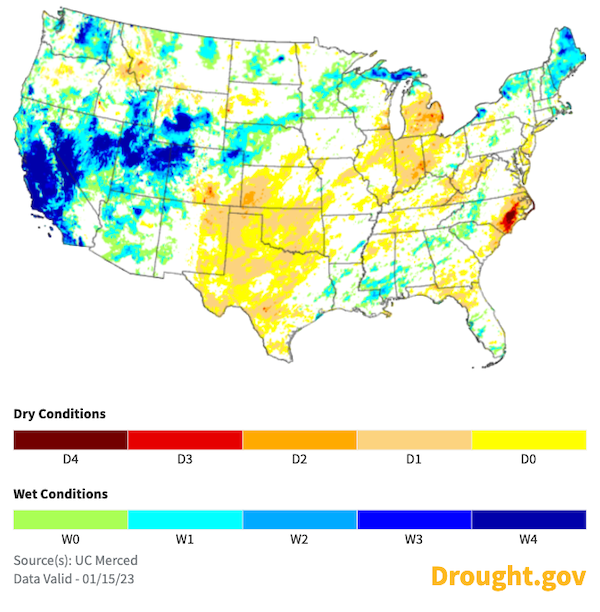

- Pockets of extreme (D3) and exceptional (D4) drought continue to persist in Utah, Nevada, and central and eastern Oregon.

- The long sequence of ARs that made landfall in California and the amounts of precipitation that fell over this relatively short period of time caused flooding, dangerous travel conditions, and debris flows.

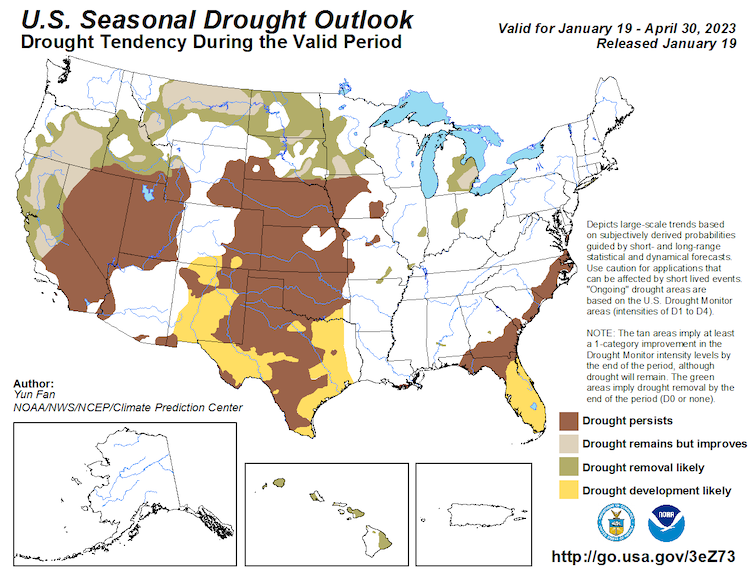

- The NOAA Climate Prediction Center's Seasonal Outlook shows chances of drought removal or improvement for central and northern California, Oregon, Idaho, and the northern Rockies, with drought remaining in southern California, Nevada, and Utah. The current forecasts indicate AR activity could pick up again in early February, but the storm tracks are still uncertain.

The U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM) is updated each Thursday to show the location and intensity of drought across the country sing a five-category system, from Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions to Exceptional Drought (D4). Drought categories show experts’ assessments of conditions related to dryness and drought including observations of how much water is available in streams, lakes, and soils compared to usual for the same time of year.

This map shows drought conditions across the western contiguous United States as of January 17, 2023.

This U.S. Drought Monitor Change Map shows where drought and dryness have improved, remained the same, or worsened in the 4 weeks from December 20, 2022 to January 17, 2023. Learn more.

U.S. Drought Monitor Categories

Abnormally Dry (D0)

Abnormally Dry (D0) indicates a region that is going into or coming out of drought. View typical impacts by state.

Moderate Drought (D1)

Moderate Drought (D1) is the first of four drought categories (D1–D4), according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. View typical impacts by state.

Severe Drought (D2)

Severe Drought (D2) is the second of four drought categories (D1–D4), according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. View typical impacts by state.

Extreme Drought (D3)

Extreme Drought (D3) is the third of four drought categories (D1–D4), according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. View typical impacts by state.

Exceptional Drought (D4)

Exceptional Drought (D4) is the most intense drought category, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. View typical impacts by state.

Classes Drought Has Degraded/Improved in the Last 4 Weeks

The U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM) is updated each Thursday to show the location and intensity of drought across the country sing a five-category system, from Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions to Exceptional Drought (D4). Drought categories show experts’ assessments of conditions related to dryness and drought including observations of how much water is available in streams, lakes, and soils compared to usual for the same time of year.

This map shows drought conditions across the western contiguous United States as of January 17, 2023.

This U.S. Drought Monitor Change Map shows where drought and dryness have improved, remained the same, or worsened in the 4 weeks from December 20, 2022 to January 17, 2023. Learn more.

Recent atmospheric rivers (NOAA: What is an atmospheric river?) have brought precipitation to the western U.S. The precipitation bolstered seasonal snowpack and improved existing drought conditions. However, the string of atmospheric rivers also caused significant flooding in many locations in California.

NOAA GOES-West Satellite Imagery: January 4, 2023

How much precipitation has fallen and where?

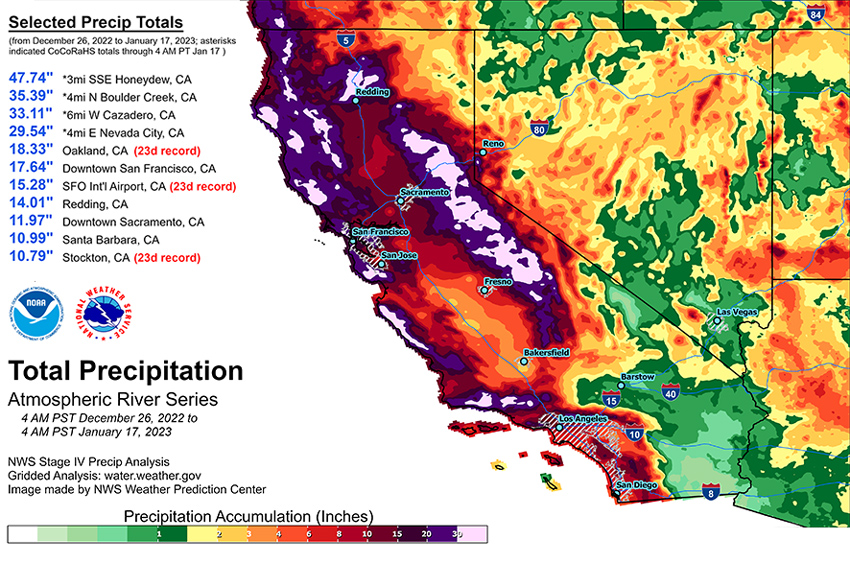

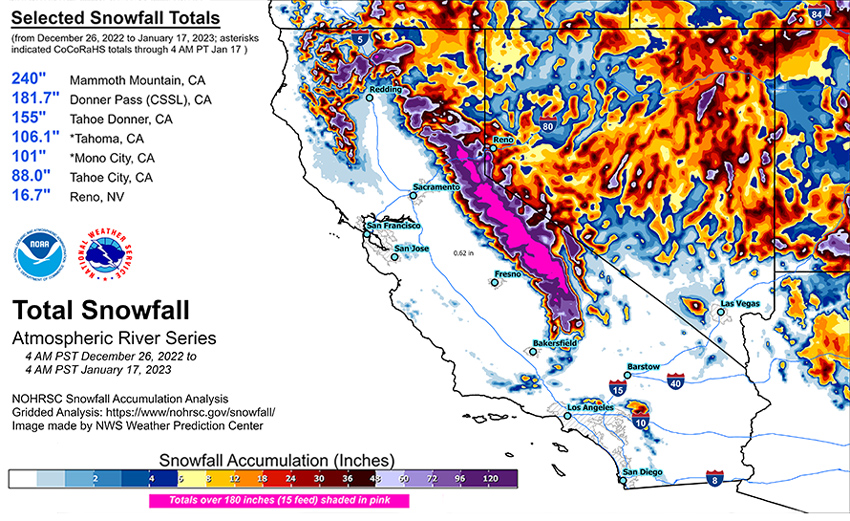

A sequence of nine atmospheric rivers made landfall along the California coast from December 26 through January 17. One of the atmospheric rivers was exceptional, four were strong, and four were moderate.

Overall snowpack is well above average in parts of the West, but it is very early in the water year. To begin to alleviate long-term hydrologic drought and contribute to spring and summer runoff, snow needs to continue to accumulate during the winter. Above-average precipitation over the next 3 to 5 years, combined with water conservation-focused resource management, would be needed to completely alleviate long-term hydrologic drought.

Notable Records:

- Multiple locations in California had the wettest 23-day period on record, including Oakland, San Francisco International Airport, and Stockton.

- Numerous daily maximum rainfall records were either broken or tied in California from December 27, 2022–January 17, 2023.

- Impressive California snowfall totals from December 27, 2022 to January 17, 2023 included 240 inches at Mammoth Mountain, 181 inches at the Central Sierra Snow Lab along Donner Pass, 106 inches at Tahoma, and 101 inches at Mono City.

- In California, 80% of a full average season of snowpack was deposited during these ARs.

Total Precipitation and Snowfall During December 26–January 17 Atmospheric Rivers

Precipitation Anomalies: Past 30 Days and Water Year to Date

Snow Water Equivalent: Western U.S.

What does this mean for drought?

Short-term drought improves.

These AR events improved short-term drought conditions in California’s Central Valley, southern California, and the Sierra Nevada mountains. In the short term, the benefits from these extraordinary storms include ample snowpack, increased top level soil moisture, and filling of reservoirs. Despite the reduction in drought severity, the intensities and rapid pacing of the ARs caused flooding and led to road closures, dangerous travel conditions, debris flows, and evacuations.

Short-Term Multi-Indicator Drought Index (MIDI)

Long-term drought remains.

Long-term drought conditions are still present as parts of the West have been in drought for more than 20 years. The impacts of long-term drought are often slow to build and recover, and can vary by location and type of drought. Severe hydrologic and ecological drought indicators—such as depleted groundwater aquifers and reservoirs and changes in the condition of plants (such as trees), ecosystem processes, and wildlife—can take months to years of normal to above-normal precipitation to recover. There is no universal drought-ending or recovery process.

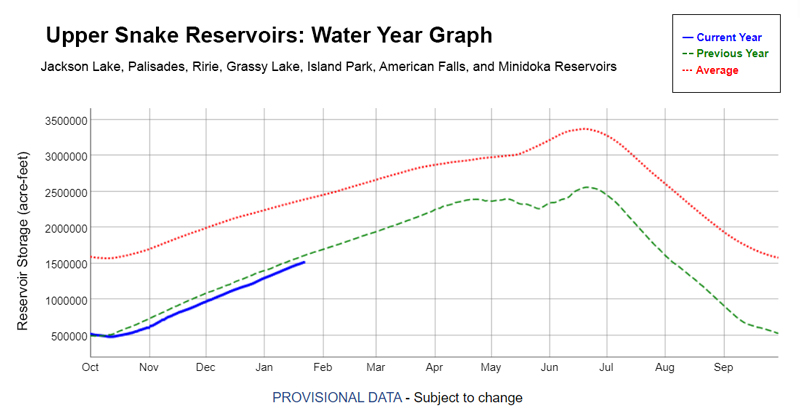

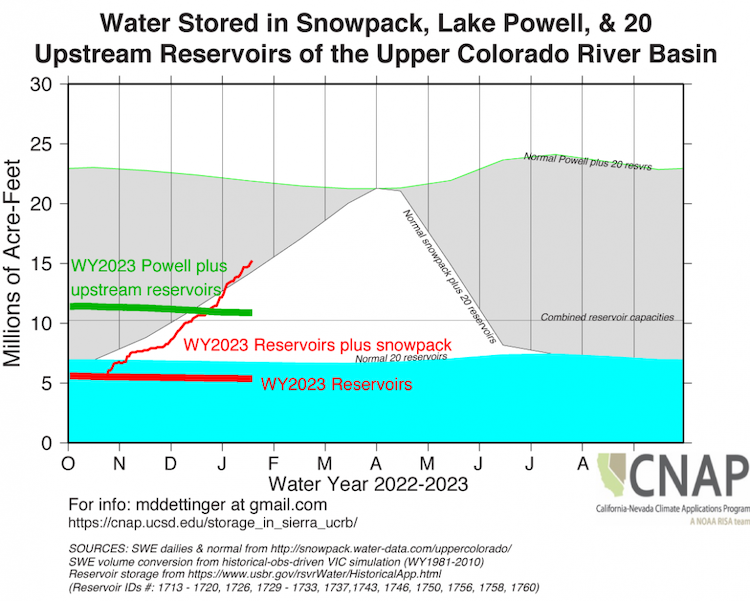

While the recent ARs provide beneficial precipitation, groundwater levels across the western U.S. remain low. Storage in many reservoirs also remains low, especially Lakes Powell and Mead in the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins, which are important for water supplies in southern Nevada, Arizona, and southern California. Reservoirs in eastern Oregon, southern Idaho, and eastern Idaho are much lower than typical for this time of year. In particular the upper Snake River basin (which contains more than 60% of the agricultural land in Idaho) is short of water, and it seems more likely than not that drought will continue for a third year in that basin.

Although short-term rain events replenish soil moisture near the surface, it can take months or years for that water to percolate into deep groundwater aquifers. Large precipitation deficits remain. In addition, whether precipitation arrives as rain or snow (due to temperature) influences how much water can be stored and then accessed during the coming dry season. Although evaporative demand (i.e., the thirst of the atmosphere) is lower during the cooler winter months, warm spells can start to dry out soils and evaporate water from reservoirs, streams, and the snowpack. Additionally, the effects of the recent drought are compounded by the impacts of warming and aridification that have occurred over the last decade and longer. Accordingly, the amount and type of precipitation that falls over the remainder of winter and spring will be very important to the occurrence and evaluation of long-term drought

Long-Term Multi-Indicator Drought Index (MIDI)

Below, we explore reservoir storage across the region.

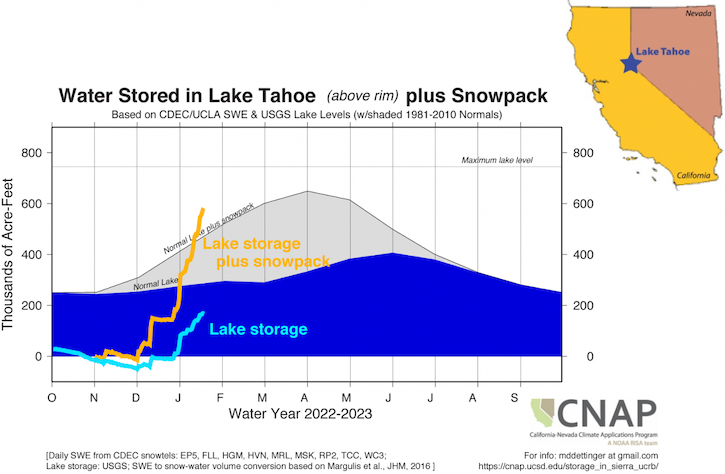

In California, the combination of snowpack and reservoir storage in the western Sierra Nevada is above normal for this time of year, and near the normal April 1 total.

In Washington, reservoir levels are near-normal. Snowpack is near-normal across most of the state with the exception of the Olympic Mountains and the northern Cascade Mountains, where it is lagging slightly below normal (81%–87% of normal).

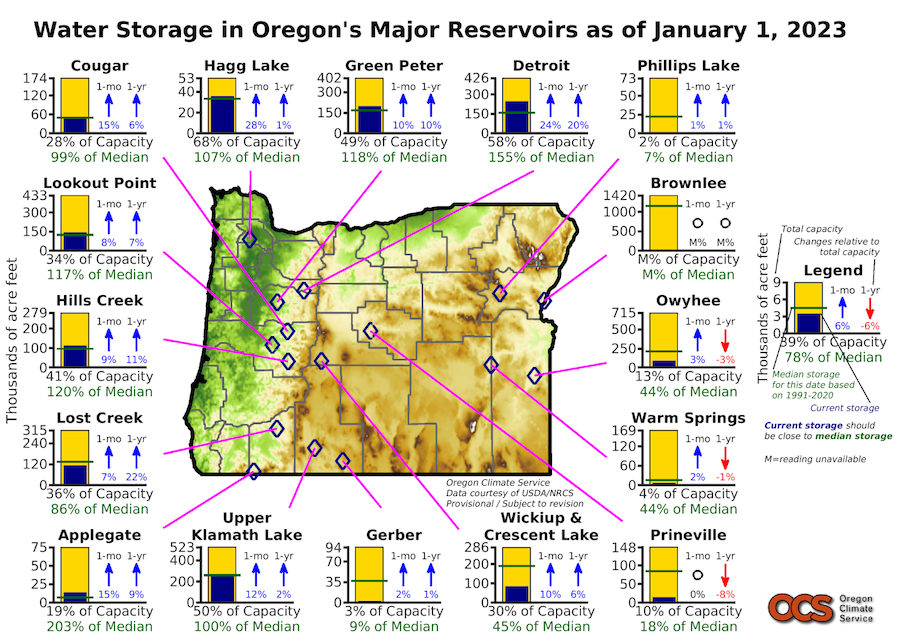

In Oregon, the amount of water stored in reservoirs has increased west of the Cascade Range, but east of the Cascade Range the situation is still dire.

In Idaho, the primary area of concern is the Snake River Reservoir System; the Upper Snake Reservoir storage is near record lows. The combined capacity of the reservoirs just exceeds 4 million acre-feet, which is slightly below the previous year.

In Nevada, the amount of water stored in lakes and reservoirs has increased appreciably since the beginning of the AR sequence. Lake Tahoe increased from very near the rim to almost 200,000 acre-feet above it, and Lahontan Reservoir storage increased by almost 50 million acre-feet.

In the Upper Colorado River Basin, the snowpack to this time of the season is very much above the 1990–2020 median, but there is still a lot of the season ahead of us. As of January 24, the Upper Colorado River Basin is at 146% of average SWE to this point of the season, but only 77% of the long-term median peak value, which usually happens around April 8. The above-normal snowpack is a cause for optimism as the spring melt will likely improve reservoir storage in the upper basin. Larger reservoirs, like Lake Powell, will need multiple above-normal seasons for meaningful improvement.

What is forecasted to happen next?

The NOAA Climate Prediction Center's 8–14 day outlooks indicate a slight tilt in the odds toward above-normal precipitation and below-normal temperatures for almost all of California and the western states. The Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes' Subseasonal Forecasts indicate greater than normal AR activity during the week of February 3–9, but the extent and storm track of these systems are still uncertain.

Given the recent precipitation and the short-range and long-range forecasts, the NOAA Seasonal Drought Outlook is showing drought removal in some parts of central and northern California, drought remaining but with improvement in other parts of northern California and central Oregon, and drought remaining but improving in Idaho. Drought persistence is expected for the remainder of southern California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and western and eastern Wyoming. Across all of the West, drought improvements or persistence will be dependent on precipitation and temperature patterns over the remainder of the winter.

There is concern about drought status in some areas of the Pacific Northwest, with drought remaining or worsening in central and southern Oregon.

8–14 Day Temperature and Precipitation Outlooks

Seasonal (3-Month) Drought Outlook

Recent Events

- Read the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes’ news, with outlooks and summaries of the recent atmospheric rivers.

- Watch the January 5 Northwest River Forecast Center’s Water Supply Forecast Monthly Briefing.

- View the January 23 California-Nevada Drought & Climate Outlook Webinar recording and summary.

Upcoming Events

- Register for the January 24 Southwest Drought Briefing Webinar.

- Register for the February 2 Northwest River Forecast Center Water Supply Forecast Monthly Briefing.

- Register for the February 27 Pacific Northwest Drought & Climate Outlook Webinar.

- Register for the March 27 California-Nevada Drought & Climate Outlook Webinar.

Drought Early Warning Resources

Pacific Northwest Drought Early Warning System

California-Nevada Drought Early Warning System

Intermountain West Drought Early Warning System

Prepared By

Joel Lisonbee

Intermountain West DEWS Regional Drought Information Coordinator, NOAA/NIDIS, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES)

Britt Parker

Pacific Northwest DEWS Regional Drought Information Coordinator, NOAA/NIDIS, CIRES

Adam Lang

Communication Coordinator, NOAA/NIDIS, CIRES

Elizabeth Ossowski

Program Coordinator, NOAA/NIDIS, CIRES

Andrea Bair, Alan Haynes, Robin Fox, & Paul Miller

National Weather Service

Joe Casola

Western Region Climate Service Director, NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information

Ryan Andrews

Oregon Water Resources Department

Mike Anderson

California State Climatologist, California Department of Water Resources

Karin Bumbaco

Office of the Washington State Climatologist, University of Washington

Erica Fleishman

Oregon Climate Change Research Institute, Oregon State University

Roger Gorke

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water

David Hoekema

Idaho Department of Water Resources

Julie Kalansky

California-Nevada Adaptation Program (A NOAA CAP/RISA team)

Larry O’Neill

Oregon Climate Service, Oregon State University

Jonathan Rutz

Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E)

Erinanne Saffell

Arizona State University

David Simeral

Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute

This special edition Drought Status Update is issued with partners from across the Pacific Northwest, California-Nevada, and Intermountain West Drought Early Warning Systems to communicate the current state of drought conditions in the seven most western CONUS states based on recent conditions and the upcoming forecast. NIDIS and its partners will issue future drought updates as conditions evolve.