Snow season ends with above-normal snowpack for much of the Northwest and Northern Rockies while the drought crisis worsens in California and the Southwest.

Key Points

- The 2021–2022 snow season has been a series of ups and downs. By early January, the dry start to the snow season was all but forgotten as snow accumulation and snow water equivalent (SWE) increased rapidly and the snowpack was well above normal. However, a long, and record-breaking in some cases, dry stretch followed the heavy December snows.

- Snow has mostly disappeared at SNOTEL sites in California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico with the exception of a few high-elevation locations.

- In the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies, snowpack remains at many sites, and SWE is above normal for this time of year due to persistent cool and wet conditions during April and May that caused a late SWE peak and slowed the snowmelt.

- Water supply remains a major concern for much of the West heading into summer 2022, especially because this is the second or third drought year in a row for many regions. Learn more about the impacts of snow drought.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) values (inches) for June 5, 2022. Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak as a percentage of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) 1991–2020 median for June 5, 2022. Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Snow Water Equivalent (Inches)

SWE Percent of NRCS 1991–2020 Median

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) values (inches) for June 5, 2022. Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak as a percentage of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) 1991–2020 median for June 5, 2022. Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Water Year 2022 Snow Drought Conditions Summary

The start of snowpack accumulation in Water Year 2022 was similar across much of the West. The season began with few major snow events, and by early December western snow water equivalent (SWE) was largely below normal. A substantial large-scale shift in the atmospheric pattern began in early December, and several weeks of cold and stormy weather across the entire West continued through New Year's. By early January, the dry start to the snow season was all but forgotten as snow accumulation and SWE increased rapidly and snowpack was well above normal. Over 200 inches of snow fell in December in parts of the northern Sierra Nevada and Donner Pass, and California received the greatest December snowfall since 1970.

Hopes were high for a snowy winter that could replenish the natural water towers of the West, but the big December snows were followed by a dry stretch that lasted one-to-two months or longer, and in some cases broke records. During that period, there was little to no snow accumulation, and snow melted in some locations. January–March precipitation totals were the lowest on record throughout the mountains of California, Nevada, southern Oregon, southern Idaho, and northern Utah, and by early March, SWE in many places was below normal again.

In the Sierra Nevada, peak SWE at many locations was below normal and occurred remarkably early in January, about two months earlier than normal. Small to moderate storms returned to some areas of the Pacific Northwest, Colorado River Basin, and northern Rockies in February and March, but there were no major storm cycles like those in December. February and March storms allowed some locations in the Colorado River and Rio Grande Basins to reach near to above-normal peak SWE; however, at the basin extent, SWE in both the Upper and Lower Colorado and Rio Grande was about 80%–85% of normal. At the start of April it appeared that peak SWE across most of the Pacific Northwest would be below normal, but then the weather pattern shifted to cool, wet, and, in the mountains, snowy during April and the first half of May. These storms added substantial water content to the snowpack in northwest Oregon, Washington, northern Idaho, and northwest Montana, where many stations reached near-normal or above-normal peak SWE several days to weeks later than normal. Southern Oregon and southern Idaho benefitted from these storms, but precipitation still was insufficient and peak SWE at most locations was below normal. The Sierra Nevada and Great Basin received beneficial snow in April, but mid-winter deficits were too large to be overcome by these storms. Instead, the storms mostly slowed the snowmelt that was already well underway. Snowpack was above normal across nearly all of Alaska this year with little snow drought concerns. However, due to low precipitation amounts since the winter snowpack meltout and periods of above-normal temperatures since late May, a large area of abnormal dryness (D0) and a pocket of moderate drought (D1) have developed in Mainland Alaska.

Snow melt at SNOTEL stations throughout the Pacific Northwest, with the exception of southern Oregon and southern Idaho, will be later than normal due to the active April and May weather. The timing of snowmelt in the northern Sierra Nevada was near normal thanks to the cool and snowy April conditions, while the southern Sierra melted out early. Snowmelt in southwest Colorado was exceptionally fast and early this year due in part to a combination of warm April temperatures and dust layers that formed in the snowpack throughout the winter.

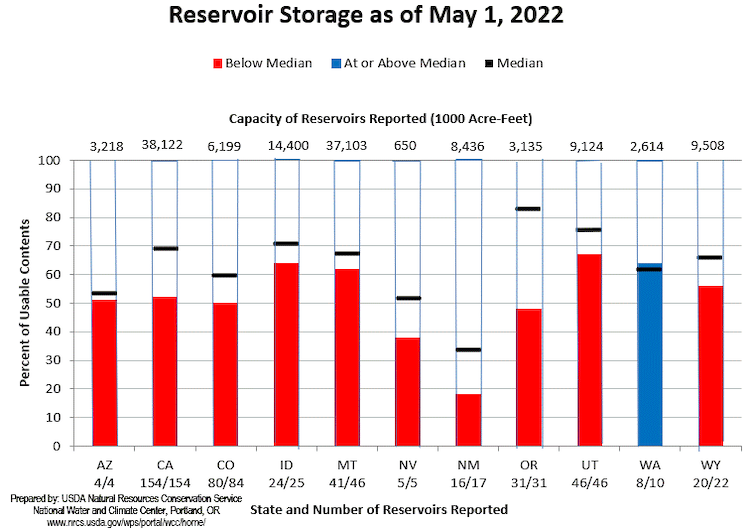

Water supply remains a major concern for much of the West heading into summer 2022, as this is the second or third drought year in row depending on the region. Statewide reservoir levels at the beginning of May were below normal water supply in all states except Washington. The two largest reservoirs in the U.S., Lake Mead and Lake Powell, are currently at the lowest levels since they were filled: both are at just below 30% of capacity. Despite water year precipitation in the Upper Colorado that was 93% of normal and peak SWE that was 83% of normal, the forecasted April–July runoff into Lake Powell is only 55% of normal. The low snowpack and early and rapid snowmelt in the Southwest and California will be a major contributor to ongoing drought impacts throughout summer and early autumn.

| HUC2 | Peak SWE % of Median | Peak SWE Date | Peak SWE Date Anomaly (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific Northwest (295 stations) | 87% | April 23 | 19 days late |

| California (27 stations) | 54% | January 21 | 64 days early |

| Great Basin (138 stations) | 69% | March 21 | 10 days early |

| Rio Grande (37 stations) | 87% | March 24 | 1 day late |

| Lower Colorado (37 stations) | 81% | March 11 | 7 days late |

| Upper Colorado (131 stations) | 83% | March 24 | 13 days early |

Table of snow water equivalent SNOTEL statistics by 2-digit hydrologic unit code (HUC) as of June 5, 2022 from the USDA NRCS.

May 1 Reservoir Storage

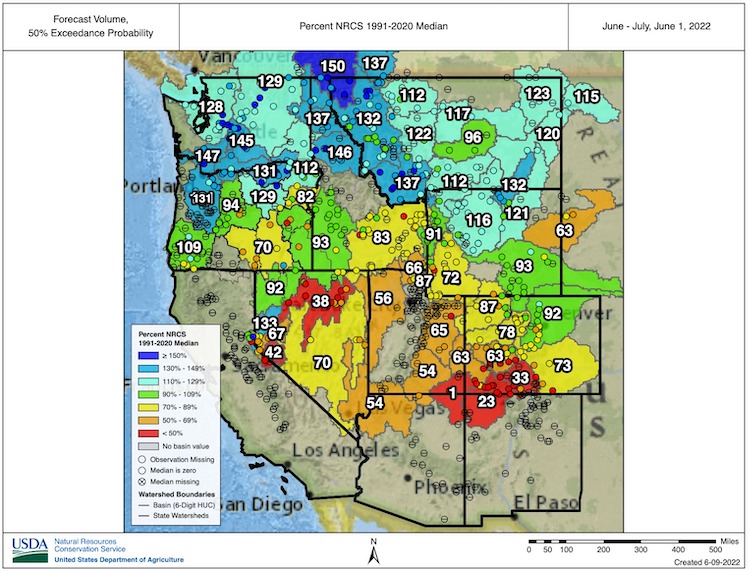

June–July Streamflow Forecast Volume for Western Watersheds

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

For More Information, Please Contact:

Daniel McEvoy

Western Regional Climate Center

Daniel.McEvoy@dri.edu

Amanda Sheffield

NOAA/NIDIS California-Nevada Regional Drought Information Coordinator

Amanda.Sheffield@noaa.gov

Britt Parker

NOAA/NIDIS Pacific Northwest and Missouri River Basin Regional Drought Information Coordinator

Britt.Parker@noaa.gov

NIDIS and its partners launched this snow drought effort in 2018 to provide data, maps, and tools for monitoring snow drought and its impacts as well as communicating the status of snow drought across the United States, including Alaska. Thank you to our partners for your continued support of this effort and review of these updates. If you would like to report snow drought impacts, please use the link below. Information collected will be shared with the states affected to help us better understand the short term, long term, and cumulative impacts of snow drought to the citizens and the economy of the regions reliant on snowpack.

Report Your Snow Drought Impacts Data and Maps | Snow Drought Research and Learn | Snow Drought