Persistent Snow Drought in Parts of the West Expected to Intensify and Expand Summer Drought Conditions

Key Points

- Snow drought conditions developed over much of the western U.S. in the first few months of Water Year 2024 due to above-normal temperatures and lack of precipitation. Some regions improved throughout the winter season (e.g., Sierra Nevada, Great Basin). Others (e.g., northern Rocky Mountains) saw snow drought persist, and outlooks predict further drought development or intensification this summer.

- In Idaho, Montana, and Washington, snow drought developed early in the season and persisted, leading to early melt out of snow and below-normal water supply forecasts.

- A series of extreme storms had major impacts on the outcomes of the snow season in the Cascade Range. Strong atmospheric rivers initially delivered considerable snow in January, followed by a major rain-on-snow event, warming temperatures, and substantial snowmelt. The early season melt event had significant impacts across many parts of the Cascade Range, notably in the North Cascades where, compounded by precipitation deficits and lack of sufficient snow accumulation through part of March and April, snow drought recovery was unlikely.

- Snow water equivalent (SWE) in most of Arizona and New Mexico was above normal throughout the accumulation season, buffering water supplies for parts of the state currently impacted by long-term drought.

- The water supply in the lower Colorado River is slightly higher than at this time in 2023, but still extremely low, with Lake Powell and Lake Mead at 38% and 34% of capacity, respectively. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is forecasting 82% of normal water year total unregulated inflows into Lake Powell.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) values (inches) for June 6, 2024. Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) 2024 water year peak as a percentage of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) 1991–2020 median. Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Drought is defined as the lack of precipitation over an extended period of time, usually for a season or more, that results in a water shortage. Changes in precipitation can substantially disrupt crops and livestock, influence the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, and affect the quality and quantity of water available for municipal and industrial use.

Learn MoreSnow drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Snowpack typically acts as a natural reservoir, providing water throughout the drier summer months. Lack of snowpack storage, or a shift in timing of snowmelt, can be a challenge for drought planning.

Learn MorePeriods of drought can lead to inadequate water supply, threatening the health, safety, and welfare of communities. Streamflow, groundwater, reservoir, and snowpack data are key to monitoring and forecasting water supply.

Learn MoreIn a drought, lower water levels or snowpack can affect the availability of recreational activities and associated tourism, and a resulting loss of revenue can severely impact supply chains and the economy. Drought—as well as negative perceptions of drought, fire bans, or wildfires—may also result in decreased visitations, cancellations in hotel stays, a reduction in booked holidays, or reduced merchandise sales.

Learn MoreDrought is defined as the lack of precipitation over an extended period of time, usually for a season or more, that results in a water shortage. Changes in precipitation can substantially disrupt crops and livestock, influence the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, and affect the quality and quantity of water available for municipal and industrial use.

Learn MoreSnow drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Snowpack typically acts as a natural reservoir, providing water throughout the drier summer months. Lack of snowpack storage, or a shift in timing of snowmelt, can be a challenge for drought planning.

Learn MorePeriods of drought can lead to inadequate water supply, threatening the health, safety, and welfare of communities. Streamflow, groundwater, reservoir, and snowpack data are key to monitoring and forecasting water supply.

Learn MoreIn a drought, lower water levels or snowpack can affect the availability of recreational activities and associated tourism, and a resulting loss of revenue can severely impact supply chains and the economy. Drought—as well as negative perceptions of drought, fire bans, or wildfires—may also result in decreased visitations, cancellations in hotel stays, a reduction in booked holidays, or reduced merchandise sales.

Learn MoreSnow Water Equivalent (Inches)

SWE Water Year Peak: Percentage of Median

< 50% of Median

The snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak is less than 50% of the median SWE value, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

50%–70% of Median

The snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak is between 50%–70% of the median SWE value, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

70%–90% of Median

The snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak is between 70%–90% of the median SWE value, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

90%–110% of Median

The snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak is between 90%–110% of the median SWE value, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

110%–130% of Median

The snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak is between 110%–130% of the median SWE value, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

130%–150% of Median

The snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak is between 130%–150% of the median SWE value, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

>150% of Median

The snow water equivalent (SWE) water year peak is greater than 150% of the median SWE value, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) values (inches) for June 6, 2024. Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) 2024 water year peak as a percentage of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) 1991–2020 median. Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

An updated, interactive version of this map is available through the USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service.

An updated, interactive version of this map is available through the USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Drought is defined as the lack of precipitation over an extended period of time, usually for a season or more, that results in a water shortage. Changes in precipitation can substantially disrupt crops and livestock, influence the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, and affect the quality and quantity of water available for municipal and industrial use.

Learn MoreSnow drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Snowpack typically acts as a natural reservoir, providing water throughout the drier summer months. Lack of snowpack storage, or a shift in timing of snowmelt, can be a challenge for drought planning.

Learn MorePeriods of drought can lead to inadequate water supply, threatening the health, safety, and welfare of communities. Streamflow, groundwater, reservoir, and snowpack data are key to monitoring and forecasting water supply.

Learn MoreIn a drought, lower water levels or snowpack can affect the availability of recreational activities and associated tourism, and a resulting loss of revenue can severely impact supply chains and the economy. Drought—as well as negative perceptions of drought, fire bans, or wildfires—may also result in decreased visitations, cancellations in hotel stays, a reduction in booked holidays, or reduced merchandise sales.

Learn MoreDrought is defined as the lack of precipitation over an extended period of time, usually for a season or more, that results in a water shortage. Changes in precipitation can substantially disrupt crops and livestock, influence the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, and affect the quality and quantity of water available for municipal and industrial use.

Learn MoreSnow drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Snowpack typically acts as a natural reservoir, providing water throughout the drier summer months. Lack of snowpack storage, or a shift in timing of snowmelt, can be a challenge for drought planning.

Learn MorePeriods of drought can lead to inadequate water supply, threatening the health, safety, and welfare of communities. Streamflow, groundwater, reservoir, and snowpack data are key to monitoring and forecasting water supply.

Learn MoreIn a drought, lower water levels or snowpack can affect the availability of recreational activities and associated tourism, and a resulting loss of revenue can severely impact supply chains and the economy. Drought—as well as negative perceptions of drought, fire bans, or wildfires—may also result in decreased visitations, cancellations in hotel stays, a reduction in booked holidays, or reduced merchandise sales.

Learn MoreWater Year Snow Conditions for the Western U.S.

Jump to Water Year 2024 snow drought conditions for your region:

- Rocky Mountain Water Year Snow Drought Summary

- New Mexico and Arizona Water Year Snow Drought Summary

- Cascade Range Water Year Snow Drought Summary

- Sierra Nevada and Great Basin Water Year Snow Drought Summary

Western U.S. Water Year to Date Precipitation Percentile (Station Period of Record)

Key Takeaway: Below-normal water year precipitation in Washington and the northern Rockies, with many locations below the 15th percentile, was one of the underlying causes of this year's snow drought. Eight stations in Montana and two in Washington saw record low values.

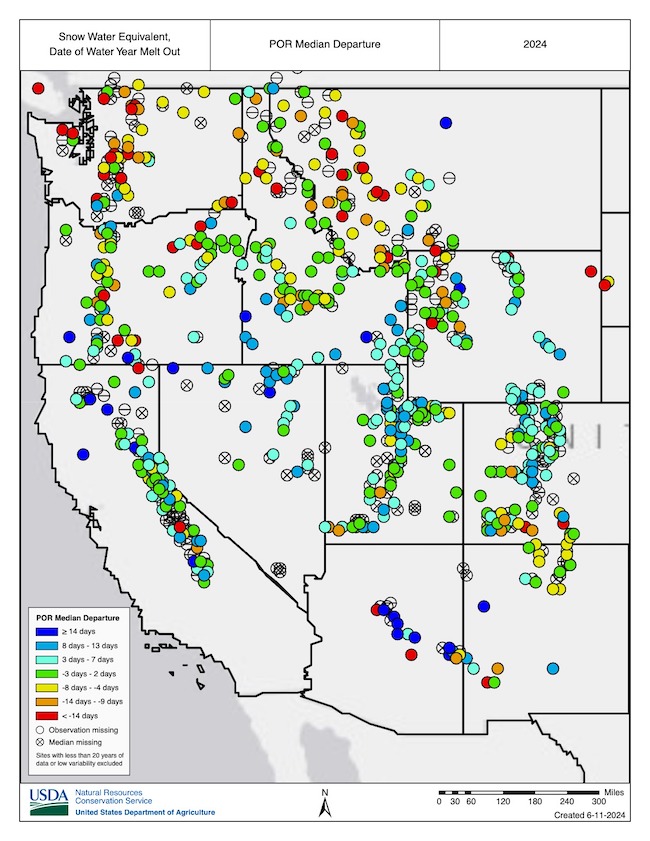

Median Departure from the Date of Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) Water Year Snowmelt

Key Takeaway: Persistent snow drought conditions and warm temperatures led to earlier than normal snowmelt (shown in yellow, orange, and red).

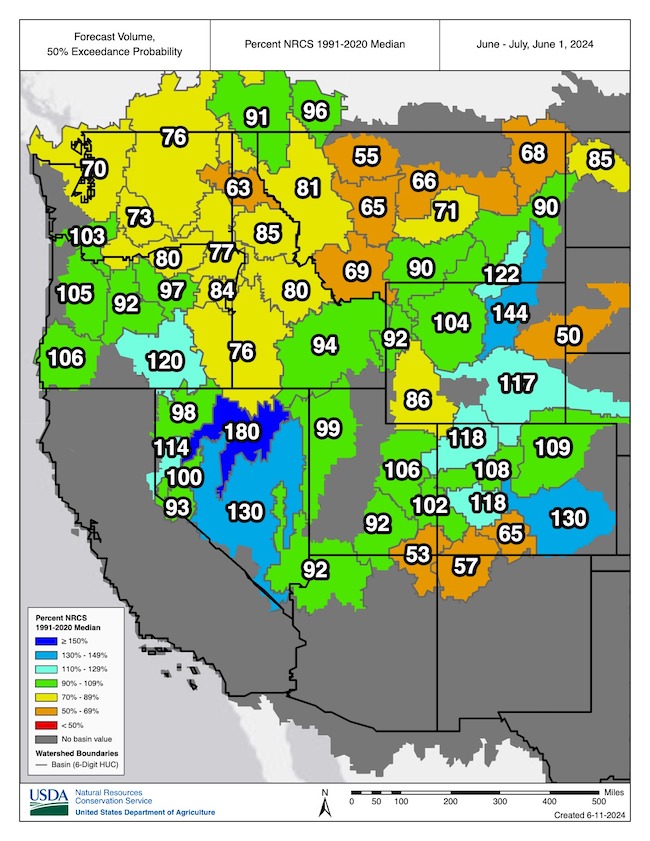

June–July Streamflow Volume Forecast

Key Takeaway: Low streamflow volumes are forecast in watersheds impacted by snow drought, including in the northern Rocky Mountains, parts of the Pacific Northwest, and near the Four Corners region.

Rocky Mountain Water Year Snow Drought Summary

Northern Rocky Mountains

Snow Drought

Snow drought conditions developed early in the season, primarily due to extremely limited precipitation, and persisted into spring. Peak snow water equivalent (SWE) in northern Idaho, western Montana, and northern Wyoming was generally 55–75% of normal. Thirteen SNOTEL stations in Montana and three in northern Wyoming had record low peak SWE. Above-normal temperatures persisted for much of the season and contributed to lower snowpack, particularly at lower elevations. Cooler than normal temperatures in the month of May, coupled with late season storms, helped to slow snowmelt and slightly increase snowpack at higher elevations. However, the low peak SWE and warm temperatures for much of the season led to early loss of snow at most SNOTEL stations (snow remains at some high elevation stations). In Montana, snow at 55 stations (77% of all stations) melted early, with many losing all snow one to three weeks early.

Water Supply Outlook

Unsurprisingly, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service’s June-July water supply forecasts indicate below-normal water volumes for most of the region. Water supply forecasts for the Missouri Headwaters, Upper Missouri, and Marias basins are among the lowest at 69%, 65%, and 55% of normal, respectively. Water supply in northern Idaho and northwest Montana generally is forecasted to be around 80–90% of normal. The exception is the Spokane Basin (including parts of eastern Washington), where 63% of normal runoff is forecasted. Moderate and Severe Drought (D1–D2) are already present in much of the region, and the poor snowpack and water supply are expected to worsen and expand drought conditions.

Central/Southern Rocky Mountains

Snow Drought

The central and southern Rocky Mountains fared much better than the northern Rocky Mountains, primarily due to a more southward shift of the storm track associated with strong El Niño conditions. A long period of warm, dry conditions in December and early January raised some concern for snow drought early in the season. The weather pattern then became more active, and snow water equivalent (SWE) across most of the region was near normal to above normal by mid-winter. Peak SWE in southern Wyoming and Colorado generally was 85–110% of normal. In northern Utah, peak SWE generally was 110–130% of normal. For sites that have lost all snow, northern Utah and northern Colorado melted out on time or late. In southern Colorado, a number of sites in the San Juans and Sangre de Cristo Mountains rapidly melted out several days to two weeks early due to spring heat waves.

Water Supply Outlook

Seasonal water supply forecasts for northern Utah and northern Colorado, including the Upper Colorado River basin, generally indicate above- to well-above normal water volumes, reflecting the healthy snowpack. The Upper Green Basin in southwest Wyoming is one area of concern, with 75–85% of normal seasonal water volumes forecast at most stream gages. Southwest Colorado and southeast Utah are also areas of concern, with 53% and 57% of normal seasonal water supply forecast for the Lower and Upper San Juan basins, respectively. Small areas of Moderate Drought (D1) are present in southwest Colorado, and the Climate Prediction Center’s U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook indicates further drought development is likely in southwest Colorado and southeast Utah.

Reservoirs in the Upper Colorado River Basin are more than halfway full, with Flaming Gorge at 87% full, Blue Mesa at 63% full, and Navajo at 72% full, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The Bureau of Reclamation forecasts 82% of normal water year total unregulated inflows into Lake Powell, which is currently at 38% of full. Though the snowpack was above average, current inflow forecasts indicate Lake Powell will likely lose any elevation it gains this spring and summer by the end of the year. The reservoir is forecast to be at 3572.92 million acre-feet, 37% full, by December 2024. Lake Mead, currently at 34% of capacity, has a similar forecast, and is expected to lose any spring elevation gains by the end of year. The actual storage may vary from this projection, primarily due to uncertainty regarding this season’s runoff and reservoir inflow.

New Mexico and Arizona Water Year Snow Drought Summary

Snow Drought

Peak snow water equivalent (SWE) across most of Arizona and New Mexico was above normal, with many locations well above normal (120–140%). Peak SWE, however, does not fully reflect conditions across the region. Arizona had little early season snow, with snow drought conditions persisting well into January. Strong El Niño conditions played a role in driving stronger storms south through Arizona and New Mexico in January and early February, rapidly increasing the snowpack. After dry conditions from early February through early March, storms returned and increased the late season snowpack. For the most part, snow melted much later than normal in central and southeast Arizona, and several days early in northern New Mexico.

Water Supply Outlook

Despite relatively high peak SWE, long-term drought and seasonal water supply shortages remain a concern. Southern New Mexico is the only area in the West with Extreme and Exceptional Drought (D3–D4) present. Much of the rest of New Mexico is in Moderate or Severe Drought (D1–D2). Areas of Moderate and Severe Drought (D1–D2) are also in Arizona. NRCS water supply forecasts for June-July total runoff are 53% and 57% of normal for the Lower and Upper San Juan basins, respectively. Moreover, the Climate Prediction Center June-August forecast favors above normal temperatures and below normal precipitation for the region. More information about Colorado River water supply forecasts is included in the Central and Southern Rocky Mountains section above.

Cascade Range Water Year Snow Drought Summary

Snow Drought

Snow drought conditions in Washington developed early in winter and intensified throughout winter and spring. This was primarily driven by large precipitation deficits from mid-winter through spring and warm temperatures throughout the season. Peak snow water equivalent (SWE) was below normal across most of Washington, with many sites in the northern Cascades and Olympics at 40–60% of normal. In Washington, snow at 44 stations (85% of all stations) melted early; one to three weeks early was typical, and several stations lost snow 40–50 days early. The snowpack in Oregon generally was higher this year than last year, although snowpack varied substantially at different elevations. Peak SWE ranged from about 80-120% of normal, and the timing of snowmelt was closer to normal in Oregon than in Washington.

A series of extreme storms had major impacts on the outcomes of the snow season across the Cascade Range. While Washington overall received less storm impacts than Oregon, the mid-winter heat wave following the initial series of atmospheric river events in early January impacted snowpack across the Cascade Range. Some locations lost 20–40% of their existing snowpack. In Oregon, where snowpack was generally near normal this winter, water year peak snowpack at some SNOTEL stations (notably at higher elevations near Mt. Hood and at some stations in central and southern Oregon Cascades) was below normal as a result of insufficient recovery from the mid-winter melt event.

Water Supply Outlook

Seasonal water supply forecasts indicate below-normal volumes across most of Washington, with 60–75% of normal forecast for much of the Cascade Range and eastern Washington. The Northwest River Forecast Center forecasts that April–September runoff volumes at many of the Washington stream gages will be in the lowest ten of all years since 1949. Water supply forecasts for Oregon are more promising than those for Washington, with most of the stream gages in the Oregon Cascade Range near normal (90–110%). Currently, 25% of Washington is classified as in Moderate Drought (D1) by the U.S. Drought Monitor, and the Climate Prediction Center’s Seasonal Drought Outlook indicates drought is likely to develop by the end of summer across most areas not currently in drought.

Sierra Nevada and Great Basin Water Year Snow Drought Summary

Snow Drought

Similar to other regions in the West, the Sierra Nevada began the year with an early season snow drought due to dry and warm conditions. Storms arrived in January and February and snowpack increased, but snow water equivalent (SWE) was still below normal. An extreme event changed the course of the snow season: a 4-day blizzard in early March rapidly pushed SWE above normal for the region, with 5–7 feet of snowfall in some locations. Water year peak SWE was generally 90–110% of normal thanks to the March blizzard. Snow generally melted on time or later than normal.

The Great Basin, including northern Nevada, southeast Oregon, and southern Idaho, had little snow drought throughout the season. Strong early December storms led to well above normal snowpack, which helped to buffer lack of precipitation during most of December. The remainder of the season was stormy, and peak SWE was generally 120–150% of normal or greater.

Water Supply Outlook

With two consecutive years of good snowpack in the Sierra Nevada and Great Basin, reservoirs are relatively full from 2023, and water supply concerns are limited. Seasonal water supply forecasts from the California-Nevada River Forecast Center show near- to slightly below-normal volumes for the Sierra Nevada. In northeast Nevada, seasonal runoff volumes are expected to be 120% to more than 150% of normal.

For More Information, Please Contact:

Daniel McEvoy

Western Regional Climate Center

Daniel.McEvoy@dri.edu

Amanda Sheffield

CIRES/NOAA/NIDIS California-Nevada Regional Drought Information Coordinator

Amanda.Sheffield@noaa.gov

Gretel Follingstad

CIRES/NOAA/NIDIS Intermountain West Regional Drought Information Coordinator

Gretel.Follingstad@noaa.gov

Jason Gerlich

CIRES/NOAA/NIDIS Pacific Northwest and Missouri River Basin Regional Drought Information Coordinator

Jason.Gerlich@noaa.gov

NIDIS and its partners launched this snow drought effort in 2018 to provide data, maps, and tools for monitoring snow drought and its impacts as well as communicating the status of snow drought across the United States, including Alaska. Thank you to our partners for your continued support of this effort and review of these updates. If you would like to report snow drought impacts, please use the link below. Information collected will be shared with the states affected to help us better understand the short term, long term, and cumulative impacts of snow drought to the citizens and the economy of the regions reliant on snowpack.

Report Your Snow Drought Impacts

Data and Maps | Snow Drought

Research and Learn | Snow Drought